By Richard McCann

Why are we not using Davis’ wealth of human capital to our advantage? Why don’t we assign, and even hire or retain, these individuals to prepare these analyses for commission review?

By Richard McCann

Why are we not using Davis’ wealth of human capital to our advantage? Why don’t we assign, and even hire or retain, these individuals to prepare these analyses for commission review?

A recent article in the New York Times by Dierdre McCloskey boldly states that the answer to income inequality is to allow unfettered growth through free market forces. Unfortunately, this thesis comes straight out of the anti-Communist 1950s. McCloskey puts up a strawman that proponents of addressing inequality directly want to redistribute all wealth via grabbing all assets of the wealthy. Her version of how the economy has worked, and the policy proposals to address inequality are incorrect.

As I posted previously, we’ve already run the experiment comparing the performance of a market-based economy (West Germany) to a centrally-planned socialist economy (East Germany), and the market-based more than doubled the output of the socialist one. That said, the past West German (and the current German) is a far cry from a “free market” economy. It was and is heavily regulated with substantial redistributive policies. No one is seriously advocating that the U.S. move to a Communist economy (at least not since the 1950s)–they are suggesting that the U.S. consider policies that could redistribute wealth to improve the welfare of almost everyone.

Increased inequality has been found to decrease economic growth, contrary to McCloskey’s implied assertion. Both the OECD and IMF found negative consequences from increased wealth in the top 20% of households. Other studies show that historic U.S. GDP growth has not been impeded by high marginal tax rates, either for individual or corporate taxes.

She also misses the real reason as to why inequality is a concern. She dismisses it as simple envy. But it’s really about relative political and economic power. The wealthy are able to exert more bargaining power in economic transactions, and their greater influence on the political process is well documented.

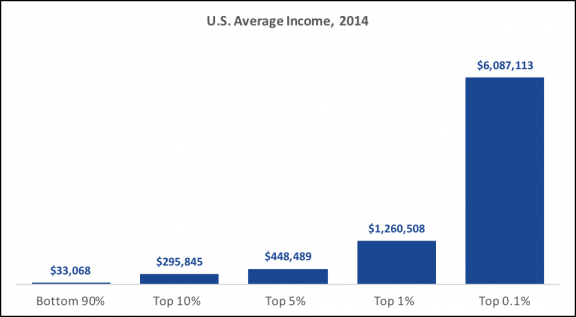

As a side note, McCloskey appears to grossly underestimating the share of wealth and income held by the wealthiest segment of U.S. society. Her calculation appears to assume that wealth is distributed evenly across all of the income quintiles (“If we took every dime from the top 20 percent of the income distribution and gave it to the bottom 80 percent, the bottom folk would be only 25 percent better off.”) In fact, a recent estimate by the Federal Reserve Board shows that the top 0.1% of U.S. households hold over 40% of the wealth. That means that redistributing the wealth of just 0.1% will lead to a 40% increase in the wealth of everyone else. I’m not advocating such a radical solution, but it does demonstrate the potential scale of redistributive policies. For example, redistributing just 25% of the wealth of the richest 1% could lead to a 10% increase in the wealth of the remaining 99.9%.

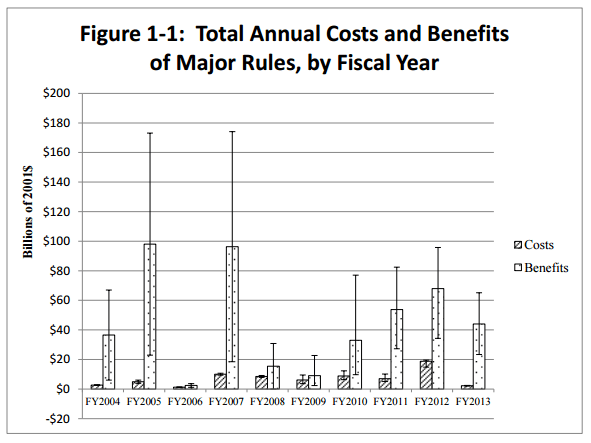

When it’s measured against $18,675 billion ($18.7 trillion) produced by the U.S. economy. The Heritage Foundation issued a report claiming the Obama Administration imposed $107 billion in new burdens over seven years. That sounds like a huge amount, but that’s only 0.6% (six-tenths of a percent) of the economy. And that’s spread over seven years which means that this the reduction in the GDP growth rate was only 0.08% (eight hundredths of a percent) per year. Against an annual average growth rate of over 2%, that’s a trivial amount. Another way to think of it is this way: if you had a dinner bill from Applebee’s for $19, would you not by dinner it if cost a dime more? Probably not–you wouldn’t even notice.

Plus, the HF’s estimate ignores the benefits of those regulations. This graphic from the OMB that shows the estimated relative benefits to costs of regulation.

I won’t dig too deeply into the Heritage Foundation’s analysis other than to make a couple of notes about about alternative perspectives that I am familiar with:

How big business and overconcentration jams the wheels of innovation in the U.S. This is particularly relevant to encouraging new distributed energy resources on the electric utility grid–the poster child for monopolies.

How big business and overconcentration jams the wheels of innovation in the U.S. This is particularly relevant to encouraging new distributed energy resources on the electric utility grid–the poster child for monopolies.

Source: Big Business Is Killing Innovation in the U.S. – The Atlantic

President-elect Trump has called for imposing significant tariffs to “bring back jobs to America.” Unfortunately, this will be a fool’s errand. The Smoot-Hawley Tariffs in 1930 were imposed to “save” farming jobs, but instead exacerbated the Great Depression as shown in the chart above. There’s no valid reason to think tariffs will work any better this time around.

Yet, there are a set of valid reasons to impose tariffs, that in a roundabout way could lead to job growth in the U.S. These tariffs could be useful tools to pursue other policy goals by forcing other nations to play on a level field with U.S. industries. The tariffs could be adjusted downward as those countries adopt policies in line with those in the U.S. The World Trade Organization (WTO) allows these types of tariffs if properly designed. Just trying to save jobs doesn’t count, but achieving valid policy goals does.

The policy areas where using flexible tariffs could be fruitful include:

Tariffs to encourage nations to comply with global greenhouse gas reduction goals is one type of environmentally oriented use. Since U.S. companies comply with a wide range of environmental regulations, many of which are intended to preserve natural habitat that has worldwide value, asking other countries to do the same seems to be a valid request. Those nations can ignore those standards if they choose, but U.S. businesses should be allowed to compete as though imported products have incurred similar compliance costs.

Similarly, the U.S. has a wide range of labor employment, workplace and safety standards. Ensuring the well being of those outside of the U.S. if we’re going to buy those products is similarly valid.

Product standards is a third area. Many U.S. products last longer and perform better because they meet stricter standards. The increased longevity of automobiles is largely a byproduct of the increased stringency of emission standards that require engine performance meet those standards for at least 100,000 miles. Improved standards also can lead to reduced waste and increased productivity.

But to justify these tariffs will require that American corporations fully support the application of these standards within the U.S. Whether they can be persuaded to the advantages remains to be seen.

Much was made during the Presidential campaign of manufacturing jobs being “exported” due to unfavorable trade pacts. Yet when we look at the data since 1960, we don’t see evidence for this claim. If jobs were being exported, then manufacturing output associated with those jobs would be leaving to. Instead, as shown above, we see that manufacturing output (and value added which is the value added to production inputs, e.g., the car value after paying for the iron, aluminum, rubber and plastic) has grown steadily with momentary dips for recessions in 1981, 2001 and 2008. Meanwhile manufacturing jobs remained fairly stable from the peak in 1979 to 2001. And then the bottom fell out: employment fell one-third from 2000 to 2009.

So if those jobs weren’t exported (obviously since the output growth was largely unchanged), then what might have happened? The chart above provides one explanation: Technological innovation replaced those jobs. The chart compares a rolling five-year average of productivity gains (measured as output per job) to sector job growth. Productivity growth had an early peak in the 1970s that coincided with the flattening of job growth through the 1990s. Then in 2001 productivity growth begins to rise to a new peak just before the Great Recession and manufacturing job growth plunges to new depths. (Note that this contrasts with the decline in overall productivity cited by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank that I posted.) Only in the last couple of years has the sector brought back jobs in the recovery.

Data from the countries where the U.S. has supposedly “exported” jobs in fact reinforces this point–they are also losing manufacturing jobs. The simple truth is that, as happened with agriculture at the turn of the 20th century, increased productivity means that fewer jobs are needed to make ever more goods. We could never feed everyone in the world if we had stopped innovation in farming in 1900; change was inevitable and largely beneficial. We can never return to the “good old days.”

Instead of trying to stop the future, we need to turn our attention to how we help those left behind by these changes. In 1900, farmers were able to move to the cities and find jobs that paid better than their farmwork. This time around, that doesn’t seem to be the case–we can’t just “leave it to the market.”

US productivity growth 1970-2015

A good overview of what drives productivity growth and why the U.S. is currently lagging compared to past periods. In essence, we have not had significant growth because we have not had technological innovations that translate into higher output. Bullard says that changes in monetary policy will not change productivity growth and suggests focusing on three areas (although he doesn’t have specific policy proposals.)

Source: Higher GDP Growth in the Long Run Requires Higher Productivity Growth

First, while these increases are eye-catching, insurers generally underpriced their plans when the marketplaces opened in 2014, and the current increases simply bring the premiums up to the level predicted when Congress debated the Affordable Care Act in 2009.According to the report, Congressional Budget Office projections from 2009 suggested average 2017 premiums of $5,538; HHS is projecting average premiums of $5,586. Indeed, premiums in many states are still below the cost of employer coverage.

Source: Don’t panic about rising ACA insurance premiums (Opinion) – CNN.com

This post seems particularly apt for the electricity industry. IOU CEOs typically are “executioners” not “visionaries,” and this is at the heart of their existential conumdrum.

What happens to a company when a visionary CEO is gone? Most often innovation dies and the company coasts for years on momentum and its brand. Rarely does it regain its former glory. Here’s why. Mi…

Source: Why Tim Cook is Steve Ballmer and why he still has his job at Apple • The Berkeley Blog

All Things Solar and Electric

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

This blog is not necessarily about biking. It's about life that is lived locally, at a human pace.

Energy, Environment and Policy

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Examining State Authority in Interstate Electricity Markets

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Economic insight and analysis from The Wall Street Journal.

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

A few thoughts from John Fleck, a writer of journalism and other things, living in New Mexico

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Tips and tricks on programming, evolutionary algorithms, and doing research

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

A blog about water resources and law

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water