More calls for keeping Diablo Canyon have coming out in the last month, along with a proposal to match the project with a desalination project that would deliver water to somewhere. (And there has been pushback from opponents.) There are better solutions, as I have written about previously. Unfortunately, those who are now raising this issue missed the details and nuances of the debate in 2016 when the decision was made, and they are not well informed about Diablo’s situation.

One important fact is that it is not clear whether continued operation of Diablo is safe. Unit No. 1 has one of the most embrittled containment vessels in the U.S. that is at risk during a sudden shutdown event.

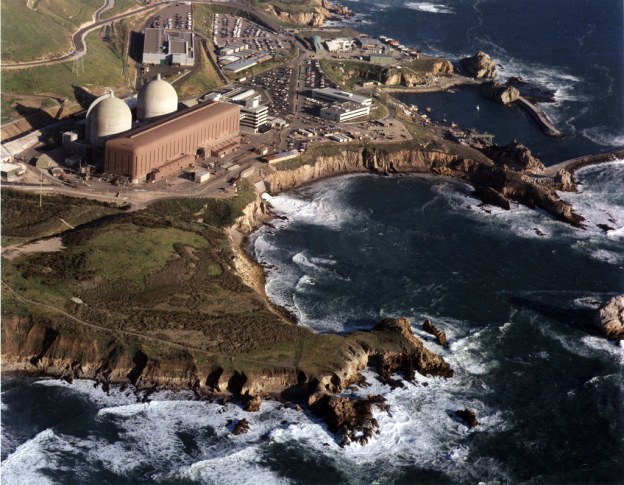

Another is that the decision would require overriding a State Water Resources Control Board decision that required ending the use of once-through cooling with ocean water. That cost was what led to the closure decision, which was 10 cents per kilowatt-hour at current operational levels and in excess of 12 cents in more likely operations.

So what could the state do fairly quickly for 12 cents per kWh instead? Install distributed energy resources focused on commercial and community-scale solar. These projects cost between 6 and 9 cents per kWh and avoid transmission costs of about 4 cents per kWh. They also can be paired with electric vehicles to store electricity and fuel the replacement of gasoline cars. Microgrids can mitigate wildfire risk more cost effectively than undergrounding, so we can save another $40 billion there too. Most importantly they can be built in a matter of months, much more quickly than grid-scale projects.

As for the proposal to build a desalination plant, pairing one with Diablo would both be overkill and a logistical puzzle. The Carlsbad plant produces 56,000 acre-feet annually for San Diego County Water Agency. The Central Coast where Diablo is located has a State Water Project allocation of 45,000 acre-feet which is not even used fully now. That plant uses 35 MW or 1.6% of Diablo’s output. A plant built to use all of Diablo’s output could produce 3.5 million acre-feet, but the State Water Project would need to be significantly modified to move the water either back to the Central Valley or beyond Santa Barbara to Ventura. All of that adds up to a large cost on top of what is already a costly source of water of $2,500 to $2,800 per acre-foot.