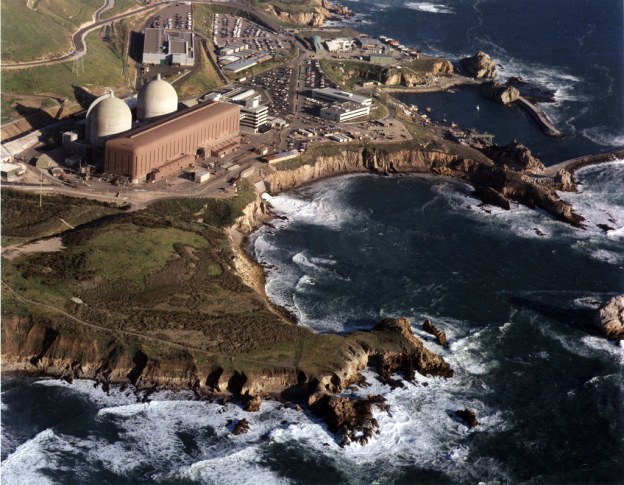

The debate over whether to close Diablo Canyon has resurfaced. The California Public Utilities Commission, which support from the Legislature, decided in 2018 to close Diablo by 2025 rather than proceed to relicensing. PG&E applied in 2016 to retire the plant rather than relicense due to the high costs that would make the energy uneconomic. (I advised the Joint CCAs in this proceeding.)

Now a new study from MIT and Stanford finds potential savings and emission reductions from continuing operation. (MIT in particular has been an advocate for greater use of nuclear power.) Others have written opinion articles on either side of the issue. I wrote the article below in the Davis Enterprise addressing this issue. (It was limited to 900 words so I couldn’t cover everything.)

IT’S OK TO CLOSE DIABLO CANYON NUCLEAR PLANT

A previous column (by John Mott-Smith) asked whether shutting down the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant is risky business if we don’t know what will replace the electricity it produces. John’s friend Richard McCann offered to answer his question. This is a guest column, written by Richard, a universally respected expert on energy, water and environmental economics.

John Mott-Smith asked several questions about the future of nuclear power and the upcoming closure of PG&E’s Diablo Canyon Power Plant in 2025. His main question is how are we going to produce enough reliable power for our economy’s shift to electricity for cars and heating. The answers are apparent, but they have been hidden for a variety of reasons.

I’ve worked on electricity and transportation issues for more than three decades. I began my career evaluating whether to close Sacramento Municipal Utility District’s Rancho Seco Nuclear Generating Station and recently assessed the cost to relicense and continue operations of Diablo after 2025.

Looking first at Diablo Canyon, the question turns almost entirely on economics and cost. When the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station closed suddenly in 2012, greenhouse gas emissions rose statewide the next year, but then continued a steady downward trend. We will again have time to replace Diablo with renewables.

Some groups focus on the risk of radiation contamination, but that was not a consideration for Diablo’s closure. Instead, it was the cost of compliance with water quality regulations. The power plant currently uses ocean water for cooling. State regulations required changing to a less impactful method that would have cost several billion dollars to install and would have increased operating costs. PG&E’s application to retire the plant showed the costs going forward would be at least 10 to 12 cents per kilowatt-hour.

In contrast, solar and wind power can be purchased for 2 to 10 cents per kilowatt-hour depending on configuration and power transmission. Even if new power transmission costs 4 cents per kilowatt-hour and energy storage adds another 3 cents, solar and wind units cost about 3 cents, which totals at the low end of the cost for Diablo Canyon.

What’s even more exciting is the potential for “distributed” energy resources, where generation and power management occurs locally, even right on the customers’ premises rather than centrally at a power plant. Rooftop solar panels are just one example—we may be able to store renewable power practically for free in our cars and trucks.

Automobiles are parked 95% of the time, which means that an electric vehicle (EV) could store solar power at home or work during the day and for use at night. When we get to a vehicle fleet that is 100% EVs, we will have more than 30 times the power capacity that we need today. This means that any individual car likely will only have to use 10% of its battery capacity to power a house, leaving plenty for driving the next day.

With these opportunities, rooftop and community power projects cost 6 to 10 cents per kilowatt-hour compared with Diablo’s future costs of 10 to 12 cents.

Distributed resources add an important local protection as well. These resources can improve reliability and resilience in the face of increasing hazards created by climate change. Disruptions in the distribution wires are the cause of more than 95% of customer outages. With local generation, storage, and demand management, many of those outages can be avoided, and electricity generated in our own neighborhoods can power our houses during extreme events. The ad that ran during the Olympics for Ford’s F-150 Lightning pick-up illustrates this potential.

Opposition to this new paradigm comes mainly from those with strong economic interests in maintaining the status quo reliance on large centrally located generation. Those interests are the existing utilities, owners, and builders of those large plants plus the utility labor unions. Unfortunately, their policy choices to-date have led to extremely high rates and necessitate even higher rates in the future. PG&E is proposing to increase its rates by another third by 2024 and plans more down the line. PG&E’s past mistakes, including Diablo Canyon, are shown in the “PCIA” exit fee that [CCA] customers pay—it is currently 20% of the rate. Yolo County created VCEA to think and manage differently than PG&E.

There may be room for nuclear generation in the future, but the industry has a poor record. While the cost per kilowatt-hour has gone down for almost all technologies, even fossil-fueled combustion turbines, that is not true for nuclear energy. Several large engineering firms have gone bankrupt due to cost overruns. The global average cost has risen to over 10 cents per kilowatt-hour. Small modular reactors (SMR) may solve this problem, but we have been promised these are just around the corner for two decades now. No SMR is in operation yet.

Another problem is management of radioactive waste disposal and storage over the course of decades, or even millennia. Further, reactors fail on a periodic basis and the cleanup costs are enormous. The Fukuyama accident cost Japan $300 to $750 billion. No other energy technology presents such a degree of catastrophic failure. This liability needs to be addressed head on and not ignored or dismissed if the technology is to be pursued.

Pingback: Obstacles to nuclear power, but how much do we really need it? | Economics Outside the Cube

Pingback: Close Diablo Canyon? More distributed solar instead | Economics Outside the Cube

More commentary on whether to close Diablo Canyon: https://www.utilitydive.com/news/analysts-differ-on-feasibility-need-to-extend-diablo-canyon-california-nuclear-plant/623214/

LikeLike

This Stanford study claiming that Diablo Canyon could be used cost effectively to produce desalinated water (https://energy.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj9971/f/diablocanyonnuclearplant_report_11.19.21.pdf) basically blows off the SWRCB regulations on once-through cooling at irrelevant to the whole situation. Academics too often waive off regulatory and political realities as irrelevant to the question at hand.

Further, I’ve calculated the ongoing cost of operating Diablo Canyon at nearly 5 cents per kilowatt-hour (submitted in a PG&E rate case proceeding and unrebutted.) And PG&E hasn’t bothered to answer the question of whether capital upgrades are required to run Diablo for another 20 years since PG&E gave up on relicensing in 2016.

In contrast, we can buy renewable power for 3 to 4 cents per kilowatt-hour, and use the existing Diablo transmission lines (which would be unused) to power that desalination plant for less.

The Stanford group, like MIT with its studies, have a fundamental interest in reviving nuclear power to further their careers and recruit students to their programs.

LikeLike

Governor Newsom considers keeping Diablo Canyon open: https://news.yahoo.com/california-promised-close-last-nuclear-130004396.html

LikeLike

PG&E will not apply for funding to continue operations: https://www.utilitydive.com/news/doe-support-program-at-risk-nuclear-plants-entergy/622420/

LikeLike