Several observers have asserted that we will require baseload generation, probably nuclear, to decarbonize the power grid. Their claim is that renewable generation isn’t reliable enough and too distant from load centers to power an electrified economy.

Problem is that this perspective relies on a conventional approach to understanding and planning for future power needs. That conventional approach generally planned to meet the highest peak loads of the year with a small margin and then used the excess capacity to produce the energy needed in the remainder of the hours. This premise was based on using consumable fuel to store energy for use in hours when electricity was needed.

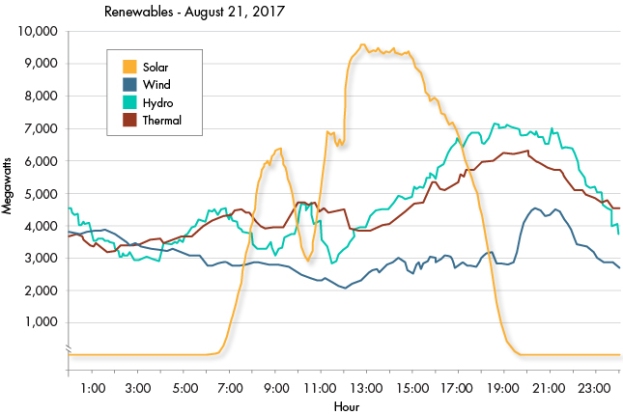

Renewables such as solar and wind present a different paradigm. Renewables capture and convert energy to electricity as it becomes available. The next step is to stored that energy using technologies such as batteries. That means that the system needs to be built to meet energy requirements, not peak loads.

Hydropower-dominated systems have already been built in this manner. The Pacific Northwest’s complex on the Columbia River and its branches for half a century had so much excess peak capacity that it could meet much of California’s summer demand. Meeting energy loads during drought years was the challenge. The Columbia River system could store up to 40% of the annual runoff in its reservoirs to assure sufficient supply.

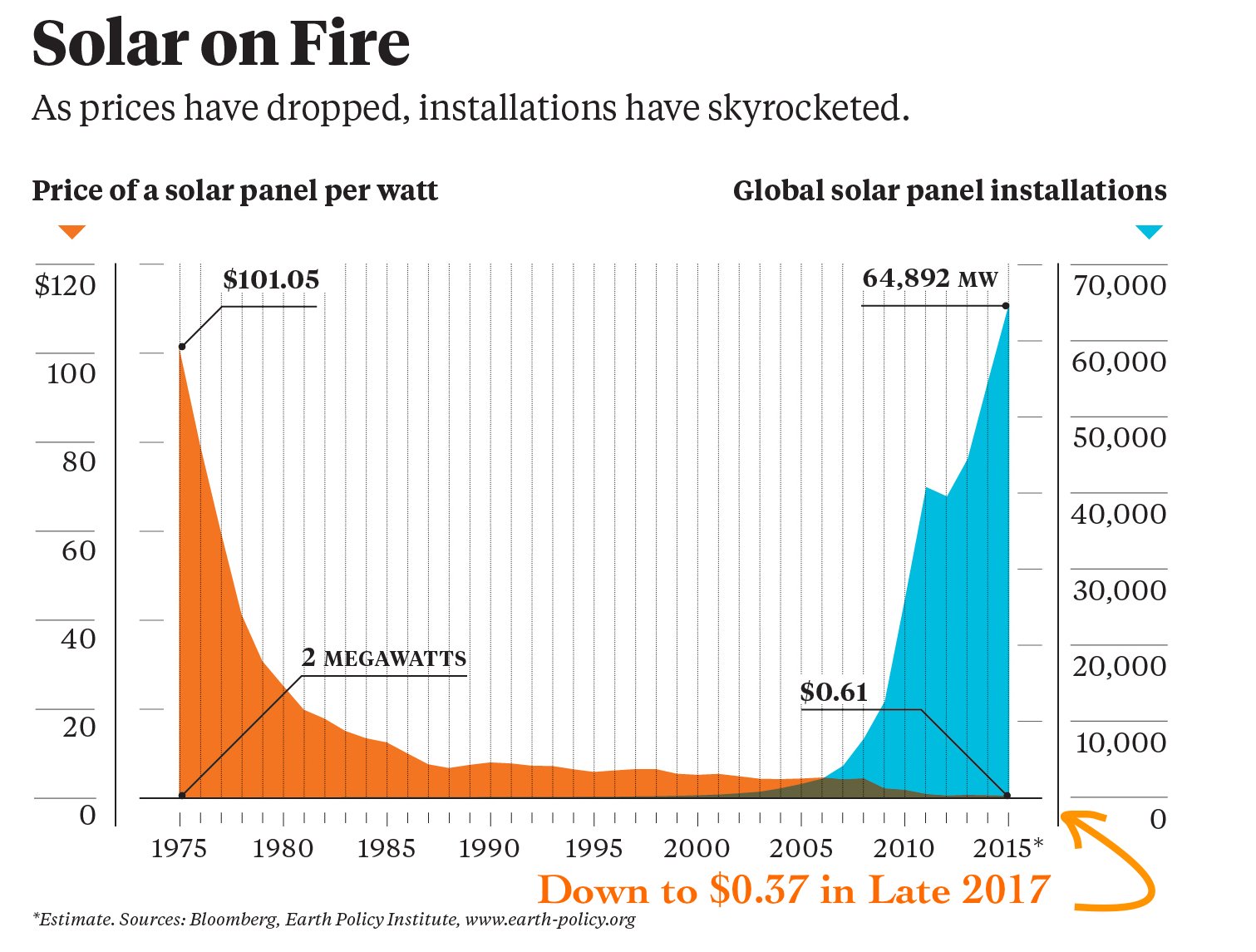

For solar and wind, we will build enough capacity that is multiples of the annual peak load so that we can generate enough energy to meet those loads that occur when the sun isn’t shining and wind isn’t blowing. For example in a system relying on solar power, the typical demand load factor is 60%, i.e., the average load is 60% of the peak or maximum load. A typical solar photovoltaic capacity factor is 20%, i.e., it generates an average output that is 20% of the peak output. In this example system, the required solar capacity would be three times the peak demand on the system to produce sufficient stored electricity. The amount of storage capacity would equal the peak demand (plus a small reserve margin) less the amount of expected renewable generation during the peak hour.

As a result, comparing the total amount of generation capacity installed to the peak demand becomes irrelevant. Instead we first plan for total energy need and then size the storage output to meet the peak demand. (And that storage may be virtually free as it is embodied in our EVs.) This turns the conventional planning paradigm on its head.