The recent reliability crises for the electricity markets in California and Texas ask us to reconsider the supposed lessons from the most significant extended market crisis to date– the 2000-01 California electricity crisis. I wrote a paper two decades ago, The Perfect Mess, that described the circumstances leading up to the event. There have been two other common threads about supposed lessons, but I do not accept either as being true solutions and are instead really about risk sharing once this type of crisis ensues rather than being useful for preventing similar market misfunctions. Instead, the real lesson is that load serving entities (LSEs) must be able to sign long-term agreements that are unaffected and unfettered directly or indirectly by variations in daily and hourly markets so as to eliminate incentives to manipulate those markets.

The first and most popular explanation among many economists is that consumers did not see the swings in the wholesale generation prices in the California Power Exchange (PX) and California Independent System Operator (CAISO) markets. In this rationale, if consumers had seen the large increases in costs, as much as 10-fold over the pre-crisis average, they would have reduced their usage enough to limit the gains from manipulating prices. Consumers should have shouldered the risks in the markets in this view and their cumulative creditworthiness could have ridden out the extended event.

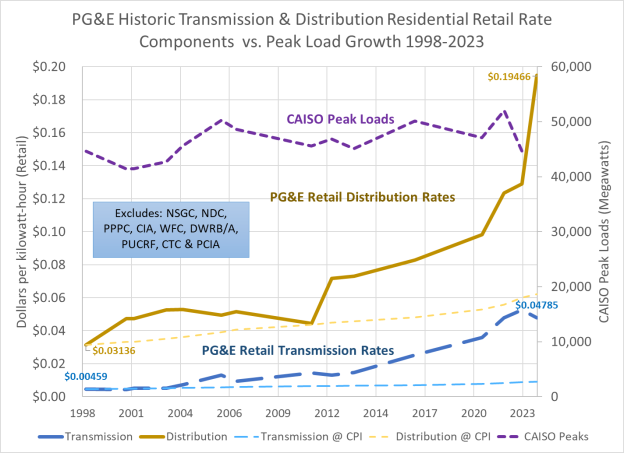

This view is not valid for several reasons. The first and most important is that the compensation to utilities for stranded assets investment was predicated on calculating the difference between a fixed retail rate and the utilities cost of service for transmission and distribution plus the wholesale cost of power in the PX and CAISO markets. Until May 2000, that difference was always positive and the utilities were well on the way to collecting their Competition Transition Charge (CTC) in full before the end of the transition period March 31, 2002. The deal was if the utilities were going to collect their stranded investments, then consumers rates would be protected for that period. The risk of stranded asset recovery was entirely the utilities’ and both the California Public Utilities Commission in its string of decisions and the State Legislature in Assembly Bill 1890 were very clear about this assignment.

The utilities had chosen to support this approach linking asset value to ongoing short term market valuation over an upfront separation payment proposed by Commissioner Jesse Knight. The upfront payment would have enabled linking power cost variations to retail rates at the outset, but the utilities would have to accept the risk of uncertain forecasts about true market values. Instead, the utilities wanted to transfer the valuation risk to ratepayers, and in return ratepayers capped their risk at the current retail rates as of 1996. Retail customers were to be protected from undue wholesale market risk and the utilities took on that responsibility. The utilities walked into this deal willingly and as fully informed as any party.

As the transition period progressed, the utilities transferred their collected CTC revenues to their respective holding companies to be disbursed to shareholders instead of prudently them as reserves until the end of the transition period. When the crisis erupted, the utilities quickly drained what cash they had left and had to go to the credit markets. In fact, if they had retained the CTC cash, they would not have had to go the credit markets until January 2001 based on the accounts that I was tracking at the time and PG&E would not have had a basis for declaring bankruptcy.

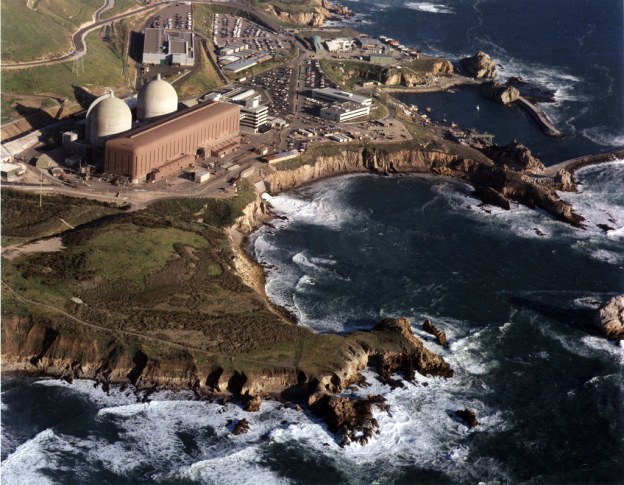

The CTC left the market wide open to manipulation and it is unlikely that any simple changes in the PX or CAISO markets could have prevented this. I conducted an analysis for the CPUC in May 2000 as part of its review of Pacific Gas & Electric’s proposed divestiture of its hydro system based on a method developed by Catherine Wolfram in 1997. The finding was that a firm owning as little as 1,500 MW (which included most merchant generators at the time) could profitably gain from price manipulation for at least 2,700 hours in a year. The only market-based solution was for LSEs including the utilities to sign longer-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) for a significant portion (but not 100%) of the generators’ portfolios. (Jim Sweeney briefly alludes to this solution before launching to his preferred linkage of retail rates and generation costs.)

Unfortunately, State Senator Steve Peace introduced a budget trailer bill in June 2000 (as Public Utilities Code Section 355.1, since repealed) that forced the utilities to sign PPAs only through the PX which the utilities viewed as too limited and no PPAs were consummated. The utilities remained fully exposed until the California Department of Water Resources took over procurement in January 2001.

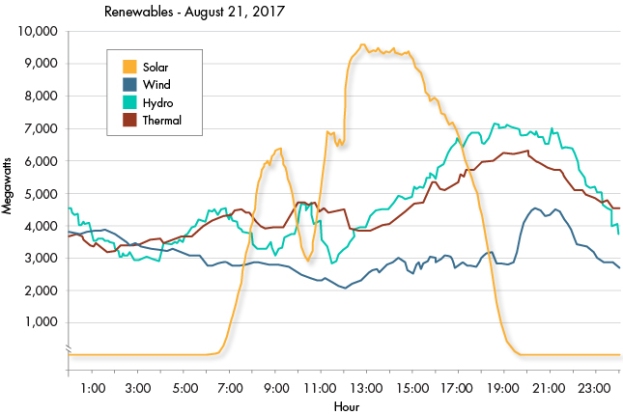

The second problem was a combination of unavailable technology and billing systems. Customers did not yet have smart meters and paper bills could lag as much as two months after initial usage. There was no real way for customers to respond in near real time to high generation market prices (even assuming that they would have been paying attention to such an obscure market). And as we saw in the Texas during Storm Uri in 2021, the only available consumer response for too many was to freeze to death.

This proposed solution is really about shifting risk from utility shareholders to ratepayers, not a realistic market solution. But as discussed above, at the core of the restructuring deal was a sharing of risk between customers and shareholders–a deal that shareholders failed to keep when they transferred all of the cash out of their utility subsidiaries. If ratepayers are going to take on the entire risk (as keeps coming up) then either authorized return should be set at the corporate bond debt rate or the utilities should just be publicly owned.

The second explanation of why the market imploded was that the decentralization created a lack of coordination in providing enough resources. In this view, the CDWR rescue in 2001 righted the ship, but the exodus of the community choice aggregators (CCAs) again threatens system integrity again. The preferred solution for the CPUC is now to reconcentrate power procurement and management with the IOUs, thus killing the remnants of restructuring and markets.

The problem is that the current construct of the PCIA exit fee similarly leaves the market open to potential manipulation. And we’ve seen how virtually unfettered procurement between 2001 and the emergence of the CCAs resulted in substantial excess costs.

The real lessons from the California energy crisis are two fold:

- Any stranded asset recovery must be done as a single or fixed payment based on the market value of the assets at the moment of market formation. Any other method leaves market participants open to price manipulation. This lesson should be applied in the case of the exit fees paid by CCAs and customers using distributed energy resources. It is the only way to fairly allocate risks between customers and shareholders.

- LSEs must be able unencumbered in signing longer term PPAs, but they also should be limited ahead of time in the ability to recover stranded costs so that they have significant incentives to prudently procure resources. California’s utilities still lack this incentive.