Severin Borenstein at the Energy Institute at the Haas Business School posted a reply[1] to our analysis[2] of the Public Advocates Office’s claim[3] of a large “cost shift” created by rooftop solar customers to other customers. Here is my extended reply to Borenstein’s critique.

- Issues of agreement: Borenstein acknowledges that the PAO used an incorrect capacity factor to calculate the total amount of rooftop solar generation. He also acknowledged that the monthly bill payments from rooftop solar customers should be included in the calculation, an error that both PAO and he has previously committed. Further, he agreed, with caveats, that the rate reductions and subsidy savings for low-income CARE customers should be included. Those elements alone add up to reducing PAO’s claimed cost shift approaching $2 billion or 25%

- Self generation: Borenstein and the PAO ignore the fact that self generation is not included in any utility resource planning. Rooftop solar generation is counted in load forecasts as a load reduction just like energy efficiency. Grid investments, generation capacity and operational decisions such as reserve margins all focus solely on metered load that excludes all self generation.. Borenstein mistakenly asserts that grid and self-provided power mingles, obviating the right to self generation. If there is generation and consumption onsite at the same time, those electrons do not touch the grid. Along with the fact that the energy does not mix, legal precedents and analysis by leading regulators contradict Borenstein’s (and PAO’s) position. Further, the NEM tariffs explicitly recognize the right to self generate for the term of the tariff.

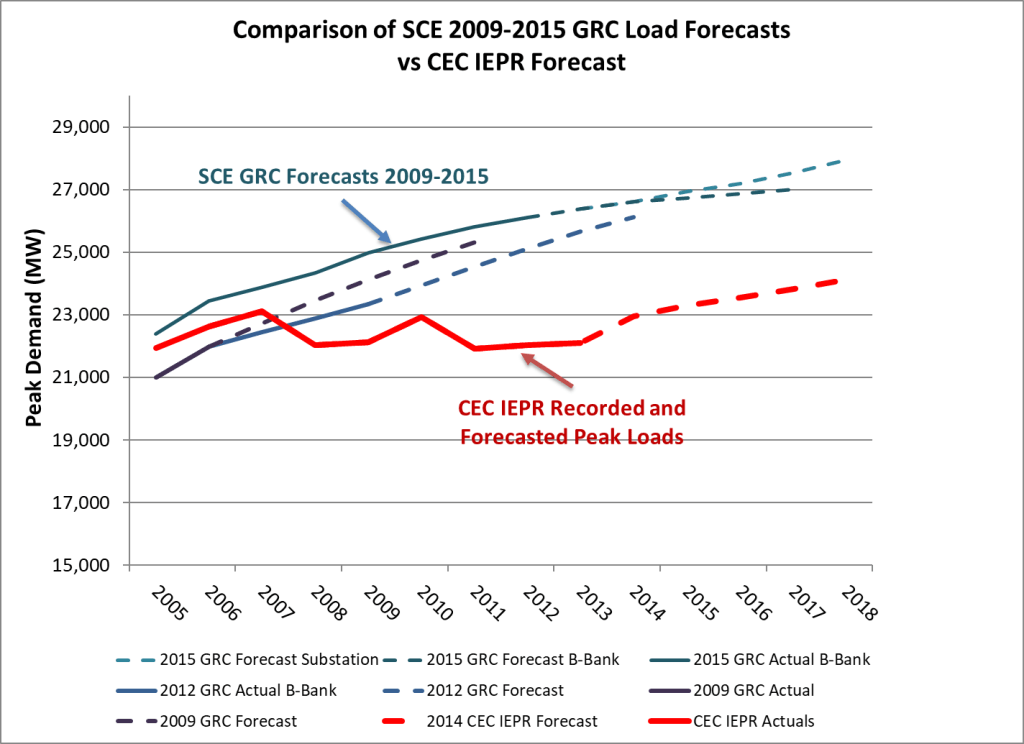

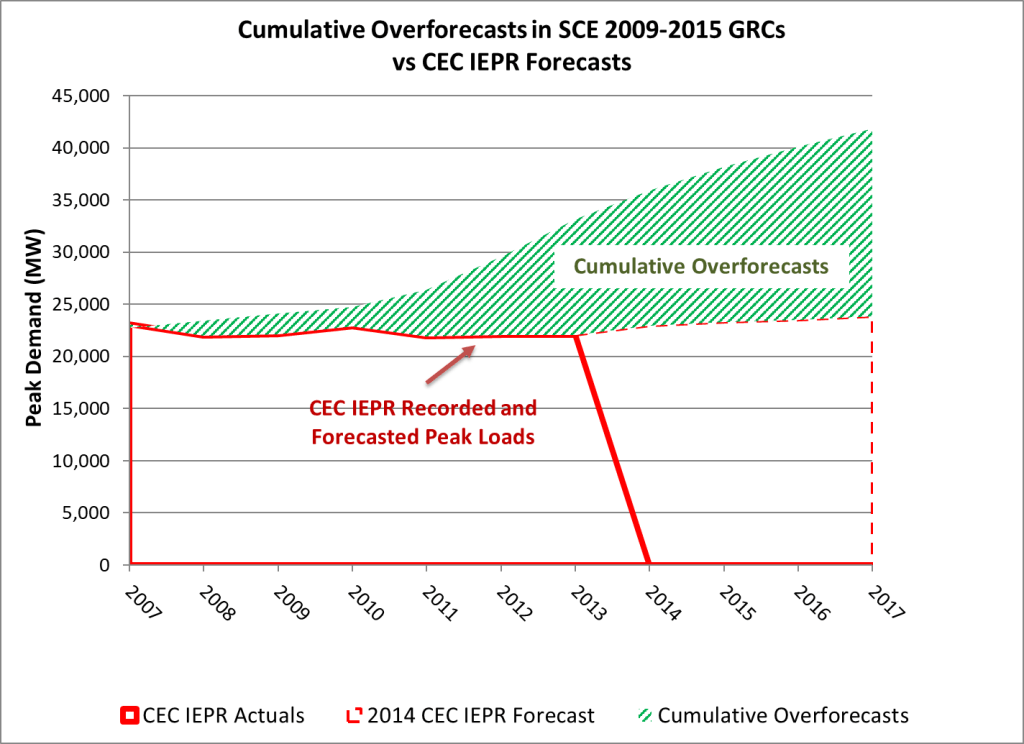

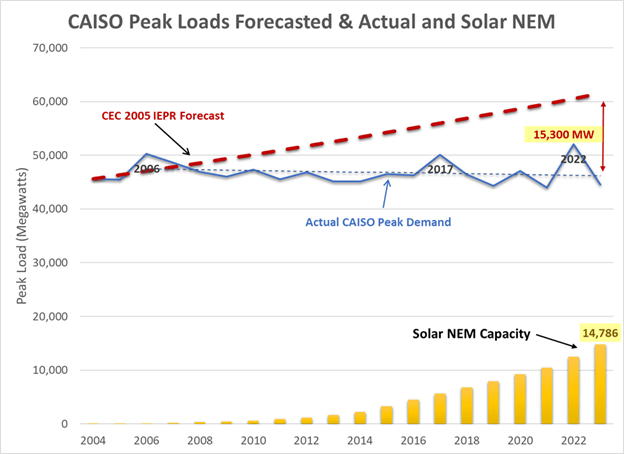

- Historic utility savings: Borenstein, like PAO, creates a confusing “apples-to-oranges” comparison of historic costs vs. projected future savings. The Avoided Cost Calculator does not include information about historic costs and therefore cannot be used to calculate historic savings from previously installed rooftop solar systems. Using this tool to estimate how much utilities would have spent were it not for previous solar installations is highly inaccurate. The ACC does not have this data. Rates do not reflect future value. In addition, Borenstein ignores suppression of peak load growth since 2006 by the addition of rooftop solar. He confuses the total customer peak served by all resources including rooftop solar with the CAISO metered peak served only by utility resources, asserting that rooftop solar provides little value to meeting today’s metered peak. Only by recreating the costs that would have been borne by ratepayers over the last two decades can the actual savings and reduction in rates be calculated.

- Customer Bill Payment: While he agrees bill payments should be included in the PAO’s analysis, but he focuses only on the cost-shift burden and fails to acknowledge the contribution to utility fixed costs made by these customers. The appropriate comparison is customer bill payments compared to utility fixed costs per customer. My analysis shows solar customers more than cover utility fixed costs.

- Overall savings provided to all ratepayers from rooftop solar conservatively is $1.5 billion in 2024.

Further observations

To start, the focus of our analysis is on the Public Advocates Office (PAO) report issued in August 2024. We used PAO’s own spreadsheet as the base of the analysis and supplemented that with other sources. The critique of Borenstein’s analysis is collateral and, compared to that of the PAO analysis, is limited to the questions of self generation and how to calculate the cost savings created by rooftop solar. His capacity factor, inclusion of CARE customers and applicable retail rates are much closer to those that I used. I pointed out in my blog post that Borenstein had not made the mistakes that PAO had made on technical issues.

Yet on the other hand, Borenstein’s own spreadsheet was documented in a small, cryptic “Readme” file,[4] and the final calculation of the “cost shift” was a set of raw values with no internal calculations. When I recreated those calculations, I could not exactly duplicate what Borenstein presented. Similarly, the PAO’s spreadsheet was sparse on documentation. Most of what is shown in my workpapers are my own additions, not PAO’s.

Finally, many of the sources that Borenstein refers to are in fact himself. The NRDC citation relies on his own Next10 report. The LAO report cites back to his own blog post. He refers to his own critique of NEM from four years ago to criticize the NEM 3.0/NBT framework that was finalized two years later. That analysis is likely now obsolete.

As for being an “industry consultant,” a sample of our recent clients shows their diversity where we have worked for environmental organizations, water districts and utilities, agricultural and business associations intervening at the CPUC, CCAs, county governments, tribes, regional energy networks, state agencies, and lately solar advocates. We must present analyses that are sufficiently balanced so as to be credible with all of these different stakeholders. Further, our work is carefully documented and our data and assumptions completely transparent, unlike the work of Borenstein or the PAO.

(I will also note that Borenstein has apparently blocked me on LinkedIn so that he can exclude me from the discussion taking place on his post there.)

[1] See https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2025/01/27/guess-what-didnt-kill-rooftop-solar/

[2] See https://mcubedecon.com/2024/11/14/how-californias-rooftop-solar-customers-benefit-other-ratepayers-financially-to-the-tune-of-1-5-billion/

[3] See https://www.publicadvocates.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cal-advocates-website/files/press-room/reports-and-analyses/240822-public-advocates-office-2024-nem-cost-shift-fact-sheet.pdf

[4] Published with his April 2024 blog post.