Davis has not been able to develop larger tracts of land to attract firms working on innovation and partnering with UC Davis. Opponents of several proposed projects have claimed that developers can instead assemble the numerous infill parcels that already exist within city limits to create the needed innovation parks. Now a new study in the leading journal, American Economics Review, finds that in Los Angeles, assembling a group of parcels for such projects faces sale prices 15% to 40% more than a single parcel project. And that doesn’t include the typical per parcel transaction costs that are compounded by multiple purchases. The bottom line is that infill development for larger projects face a high cost premium that must be acknowledged.

Davis has not been able to develop larger tracts of land to attract firms working on innovation and partnering with UC Davis. Opponents of several proposed projects have claimed that developers can instead assemble the numerous infill parcels that already exist within city limits to create the needed innovation parks. Now a new study in the leading journal, American Economics Review, finds that in Los Angeles, assembling a group of parcels for such projects faces sale prices 15% to 40% more than a single parcel project. And that doesn’t include the typical per parcel transaction costs that are compounded by multiple purchases. The bottom line is that infill development for larger projects face a high cost premium that must be acknowledged.

Tag Archives: innovation policy

An answer to Brexit & Trump: Rebuild our infrastructure

At the core of the dissatisfaction driving support for Brexit, Donald Trump (and Bernie Sanders) is economic dislocation that reduced the jobs and wages of those who worked in the manufacturing and construction industries. The solution is NOT to return to retail manufacturing, where the U.S. can’t compete with China; nor is it to extract more fossil fuels in a highly volatile energy market or to build houses for another financial bubble. Instead we can address their needs while solving a different crisis–fixing our crumbling infrastructure, and even get some other ancillary benefits. We would have both construction and heavy manufacturing jobs with good wages, aimed right at the Brexit/Trump constituencies. And there would be little foreign competition while we put the U.S. economy on better footing to compete in other sectors.

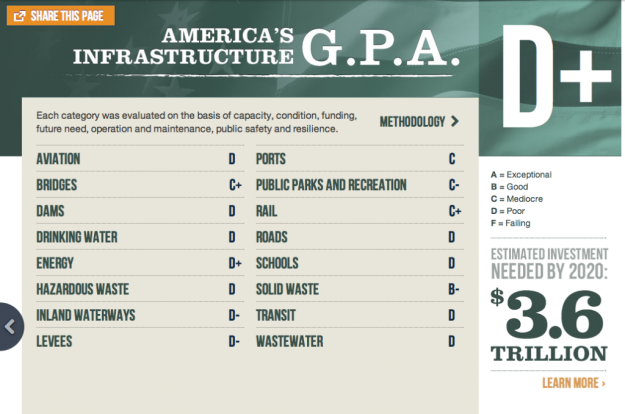

The American Society of Civil Engineers estimate that America needs $3.6 trillion of investment in replacing our infrastructure such as roads, waterworks, power and gas lines and the rest that makes American go. This sounds like a big number, but it’s only a bit more than half of what all federal, state and local governments spend annually. Of course, we would never pay for all of this at once. In our current low-interest environment, at 3% bond financing over 30 years, the annual cost would be $180 billion, which is less than 3% of total spending.

The key is to use disciplined deficit spending, i.e., bonded indebtedness, to finance this program. Funds should be earmarked specifically for this program at the federal, state and local levels. One source of funds could be a wealth tax. A tax rate of 0.2% (yes, two tenths of a percent) on registered securities and real estate could cover the annual debt repayments.

We could tie this program to two other possible goals:

- To ensure that the income from holding the bonds accrue to a wider segment of the population, we could limit purchase of the bonds to the Social Security Administration and widely-held municipal bond mutual funds.

- We could staff the program with young people serving in a compulsory national service. The national service would give 18-20 year olds their first jobs and bring together a mix of different backgrounds and cultures. As the draft did in World War II, they could gain a better understanding of others beyond their current experiences.

Nishi and Our Obligations to Other Californians

I wrote this column for the Davis Vanguard in a series about the future of economic development for Davis:

The University of California created what Davis is today. When UC Davis became a full-fledged campus in 1959, the State of California began the process of pouring resources into this city to develop a top notch university. UC Davis is now acknowledged as the top agricultural academic institution in the world.

We can see what the university has brought us all around. If you want to imagine what Davis would look like without UCD, go to Woodland or Dixon. We have a vibrant downtown with many community activities. We have one of the top rated school systems in the state. And our property values reflect the premium of those benefits. Davis is a very desirable place because of UCD. You have chosen to live here because of these amenities that cannot be readily found elsewhere in the Central Valley.

State taxpayers have contributed billions of dollars over the years to the campus, and students have brought resources from around the state, keeping the local economy vibrant. In return, the state has not asked Davis explicitly for any contributions or cooperation. Yet there are obligations that come with hosting UCD. Other state residents are counting on UCD, and its host city, to provide an educational gateway to both UC students and concomitant economic and cultural growth statewide.

How do we meet that obligation? By providing a fair share of housing to students, and affordable housing for faculty and staff. By incubating new businesses that spin off innovations developed on campus. And by cooperating with UCD in its long-range plans. Yes, we need to ask reasonable cooperation from the University in return (which does not always come readily. For example, I opposed the final configuration of West Village, and believe part of its difficulties arise from that configuration.) But that does not mean that we can oppose all UCD-related development.

So how does the Nishi Gateway Project relate to this obligation? UCD cannot and should not host all housing and spin offs on campus. Students need to learn how to live on their own outside of the protective UC womb. And UCD should not be directly involved in commercial activity because that puts the state directly in the role of promoting certain profit-making enterprises. Instead, the city needs to host housing and businesses. Other college towns successfully accomplish these tasks.

Davis is the only significant university town without a large research park; this puts UCD at a distinct disadvantage for attracting research dollars and researchers. And UCD is at a disadvantage recruiting faculty. Many assistant and associate professors have spouses working in technical fields, and universities usually help them find jobs as part of recruiting. Davis lags in offering these opportunities. Nishi will create jobs for this younger adult segment, both for incoming faculty’s families and for graduating students. Davis is already experiencing a hollowing out of our young adults population; we need to reverse this trend to keep the town vibrant.

Nishi offers a mix of research and development space and housing close to campus that meets most of our standards for sustainability and impacts. It may not offer the “perfect and optimal” configuration, but no one can ever achieve that standard, simply because that definition varies in the eye of the beholder. Creating affordable housing is about much more than just designating a few units for lower income residents. A constrained housing market guarantees higher prices—just ask San Francisco and Manhattan. The best way to make housing more affordable in Davis is to offer more housing. Nishi does this in the context of a relationship with our biggest employer.

Some suggested that alternative locations exist for this development, that residents will be exposed to excessive pollution, or that we will be losing agricultural land. First, the process of assembling the parcels needed for this scale of project is much more difficult and expensive than opponents realize. Controlling the land is key to success. Second, I have not heard anyone objecting to the new housing developments along Olive Lane, yet they experience the same environmental exposures; the same can be said about much of South and West Davis. And third, farming is no longer economically viable on Nishi. Its isolation makes agricultural activities too expensive—it is time to move on.

Instead, we need to ask if this development is not approved, what will be built instead? We have already seen the type of developments popping up in West Sacramento, Roseville, Elk Grove and even “north North Davis”, i.e., Spring Lake in Woodland. As Davis suppresses growth here, less desirable developments pop up there. Are we really “thinking globally, acting locally” when we close down any new developments by demanding perfection? We cannot return to the bucolic days of the University Farm. Let’s keep real control of our future instead of pushing it off to someone else.

Richard McCann is a member of the City’s Utilities Rates Advisory Committee and Community Choice Energy Advisory Committee. He is a partner in M.Cubed, a small environmental and resources economic consulting firm. His opinions are solely his own and are not endorsed by URAC or CCEAC.

On Mankiw: The shrinking pie slice

Gregory Mankiw observed how many political standards this year are myths. I don’t agree with all of them, but one particularly jumped out at me. He noted that manufacturing output is up 47% over the last 20 years, but employment is down by 29%. His point is that increased productivity is good and needed to improve our standard of living, and I agree with his presumption.

That would be all fine and good if those gains had rolled through to workers to a significant degree. If all of the gains had gone to labor, wages and benefits should have gone up by 107% over twenty-years–more than double. However, looking at the Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Cost Index (which includes benefits as well as wages), total wages and benefits rose only 71% over that period. The other 37% accrued to the owners of the manufacturing firms. It’s that shift in the balance of benefits from productivity that is driving political discontent, as I wrote about earlier. Labor’s share of the growing pie is shrinking.

Getting to the harder question about stranded assets

John Farrell at the Institute for Self-Reliance argues that existing utility fossil-fuel plants should not be given “stranded assets” status. While his argument about “stranded assets” makes sense from a society wide economic sense, it doesn’t conform with the utility regulation world in which “stranded assets” is actually relevant. Having gone through California’s restructuring and competitive transition charge (CTC) (I’m the only person outside of the utilities to conduct a complete accounting of the CTC collection through 2001), it’s all about what’s on the utility’s books and what the regulatory commission agrees is an acceptable transfer of risk. And based on what happened with Diablo Canyon in 1996 (the correct treatment would have recognized that PG&E had collected its entire investment at the regulated rate of return by 1998—I did that calculation too), it’s not promising.

So I suggest focusing on the shareholder/ratepayer risk sharing arrangement and how that should be changed in the face of the oncoming utility 2.0 transformation as a more fruitful path. We have to change the underlying paradigm first. That there are benefits from retiring generation assets is not a hard argument to win—that was the case in 1996 in California. The harder one is that the past regulatory compact should be changed and that it won’t somehow impact future investment in the distribution utility.

Today’s rise of populism and loss of economic opportunity

Robert Reich, the former Secretary of Labor, now UC Berkeley professor, and Friend of Bill (Clinton) wrote about how he found he agreed with the basic points of Tea Party supporters:

For example, most condemned what they called “crony capitalism,” by which they mean big corporations getting sweetheart deals from the government because of lobbying and campaign contributions…The more conversations I had, the more I understood the connection between their view of “crony capitalism” and their dislike of government. They don’t oppose government per se. …Rather, they see government as the vehicle for big corporations and Wall Street to exert their power in ways that hurt the little guy. They call themselves Republicans but many of the inhabitants of America’s heartland are populists in the tradition of William Jennings Bryan.

Eliana Johnson, a conservative columnist at the National Review, made a similar observation on NPR:

I actually think Donald Trump is really an embodiment of blue-collar frustration with what are really a bipartisan elite consensus on a number of issues that Republicans and Democrats in Washington agree on. One is free trade, and you see Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders taking similar positions there reflecting frustration. Another is immigration, where Donald Trump is an ardent opponent of letting more immigrants into the country. And I think you see the far left and the far right coming together on that issue. And so Barack Obama is certainly an embodiment of elite Washington opinion, but it’s really, I think, frustration among the grassroots of both parties about issues, really, that Republicans and Democrats agree on and where they feel they are not getting a hearing.

The first question is what is at the heart of the frustration among the white middle-class that is at the core of the Tea Party, and support for Donald Trump. Essentially the white middle class sees that the social compact that guaranteed a comfortable life style with little uncertainty by simply working steadily has come apart. The Great Recession accelerated a trend that was already gaining steam as unemployment and underemployment for older white men increased. Job security for a group that historically has enjoyed the greatest job security is disappearing. And they’re angry about it.

The next question is what is at the core of this trend. First a digression into what we do for “work.” Typically we can divide up what we work on into three areas: making things used by other people, directly serving people, and creating ideas and concepts that people can enjoy or use in the other two work areas. There are physical limits on the value that any one worker can create either in manufacturing or in services. A factory worker can produce only one car at a time and a consumer can buy and use only one car. A coffee barista can serve only one customer at a time, who in turn can only drink one coffee at a time. Nobel Prize winner William Baumol identified this “cost disease” 50 years ago, but he was focused only on services versus manufacturing. He observed that technology could help the factory worker make a car faster, but it wouldn’t be much help for a coffee barista. But he hadn’t considered the role of workers who create ideas and concepts, simply because this wasn’t a big part of the economy then.

With the advent of computers and the Internet, along with other mass media, it’s now possible for a “worker” such as an entertainer, an athlete, an investment banker, or an app programmer, to create a “product” that can be consumed by millions with no limitations on how many can buy and use that product at one time. Distribution of the product is now almost costless. As a result, a single worker can create huge amounts of economic value single-handedly. That’s not the case with either manufacturing or services. The workers in the ideas and concepts industries can now command extraordinary salaries. Bay Area tech workers are earning an average of $176,275!

Who are these tech workers? Not older white middle class men with a high school education or less. Instead economic value is accruing to the younger, college educated (particularly in STEM fields) and the “middle class” is disappearing. The supporters of the populist causes and the demagogues who exploit those opportunities are those being left behind by this radical transformation of the economy.

The same thing happened at the turn of the twentieth century as the nation moved from an agrarian economy with a 38% of its population on the farm to an industrial powerhouse. William Jennings Bryant thrice ran for President as a populist, in his time railing against the gold standard and calling for “free silver.” His supporters were the farmers being left behind by rapid economic change.

As was the case then, the older dominant labor force working in traditional, stable industries today are not well equipped to adapt to the coming of disruptive changes. They have been extolled as the core of a virtuous workforce, as was the case with farmers then, so they have become part of the American pantheon. Just watch any pickup truck commercial. They understood the social compact as putting in a 40-hour week being sufficient to deliver a comfortable lifestyle. These workers understood that they wouldn’t have to change their careers or learn new skills to live the “American dream.” Unfortunately, that was a false promise. (We can’t really expect that everyone should understand how the economy works–at least not without major changes in our education and media systems.)

Now they look for “easy solutions” of the type long offered by politicians, and they are not disappointed by the offerings. Blocking immigration, imposing trade restrictions, and creating opportunity are all buzz word solutions without real substance or a likelihood for success in solving their problems (and may make the problems worse.)

The change a century ago led to economic benefits that few would dispute improved the well-being of most Americans; we would not have wanted to freeze the proportion of the U.S. economy devoted to agriculture. The final question then is what should be the appropriate policy responses to mitigate these harsh effects on a group that long enjoyed a favorable position in our economy while allowing for another beneficial economic transformation?

The decisions utilities must make soon

Jeff McMahon at Forbes wrote a nice two-part series on the existential decisions that utilities face going forward. Part 1 is here, and Part 2 here. I posted earlier a longer article from the New Yorker looking at the changing landscape.

Robotics and our future workforce

I mentor a competitive high school robotics team (which recently won the FIRST World Championship). I work with these students because I see that we must develop them to participate effectively in the future workforce. So I saw with interest this month that both the Atlantic Monthly and the Journal of Economic Perspectives ran articles on how increasing use of robots could reduce, or even eliminate, the need for humans working. The Atlantic has long been running a series of articles on the issue; a 2011 article in particular piqued my interest in with working with Citrus Circuits.

The utility revolution hits the mainstream

This New Yorker article, “Power to the People,” is one of the first mainstream press articles discussing how the energy utility landscape is being transformed. (This was sent to me by one of my non-energy clients.) It prompted one thought: the “death spiral” only occurs if we hold on to the traditional model of utility investment and regulation. Allowing utility shareholders to participate in the transformation through their unregulated holding companies can mitigate much of the potential for a death spiral.

Repost: Deconstructing the Rosenfeld Curve

Deconstructing the Rosenfeld Curve.

By Lucas Davis on Energy Insitute at Haas

Are California’s energy efficiency standards a useful rubric for other states?