M.Cubed partner Steven Moss wrote this editorial “Publisher’s View: Pacific Gas and Electric Company” in the Potrero View on how PG&E might move forward into the future.

M.Cubed partner Steven Moss wrote this editorial “Publisher’s View: Pacific Gas and Electric Company” in the Potrero View on how PG&E might move forward into the future.

Severin Borenstein at the University of California’s Energy Institute at Haas posted on whether a consumer buying an electric vehicle was charging it with power from renewables. I have been considering the issue of how our short-run electricity markets are incomplete and misleading. I posted this response on that blog:

As with many arguments that look quite cohesive, it is based on key unstated premises that if called into question undermine the conclusions. I would relabel the “correct” perspective as the “conventional” which assumes that the resources at the margin are defined by short-run operational decisions. This is the basic premise of the FERC-designed power market framework–somehow all of those small marginal energy increases eventually add up into one large new powerplant. This is the standard economic assumption that a series of “putty” transactions in the short term will evolve into a long term “clay” investment. (It’s all of those calculus assumptions about continuity that drive this.) This was questionable in 1998 as it became apparent that the capacity market would have to run separately from the energy market, and is now even more questionable as we replace fossil fuel with renewables.

I would call the fourth perspective as “dynamic”. From this perspective these short run marginal purchases on the CAISO are for balancing to meet current demand. As Marc Joseph pointed out, all of the new incremental demand is being met in a completely separate market that only uses the CAISO as a form of a day to day clearinghouse–the bilateral PPAs. No load serving entity is looking to the CAISO as their backstop resource source. Those long term PPAs are almost universally renewables–even in states without RPS standards. In addition, fossil fueled plants–coal and gas–are being retired and replaced by solar and wind, and that is an additional marginal resource not captured in the CAISO market.

So when a consumer buys a new EV, that added load is being met with renewables added to either meet new load or replace retired fossil. Because these renewables have zero operating costs, they don’t show up in the CAISO’s “marginal” resources for simple accounting reasons, not for fundamental economic reasons. And when that consumer also adds solar panels at the same time, those panels don’t show up at all in the CAISO transactions and are ignored under the conventional view.

There is an issue of resource balancing costs in the CAISO incurred by one type of resource versus another, but that cost is only a subcomponent of the overall true marginal cost from a dynamic perspective.

So how we view the difference between “putty” and “clay” increments is key to assessing whether a consumer is charging their EV with renewables or not.

A study in the Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economics entitled “External Impacts of Local Energy Policy: The Case of Renewable Portfolio Standards” finds that increasing the renewable portfolio standard (RPS) in one state reduces coal generation in neighboring states through trading of renewable energy credits (RECs). This contrasts with findings on greenhouse gas emission “leakage” under California’s cap and trade program put forth by the authors at the Energy Institute at Haas at the University of California here and here.

These latter set of findings has been used California Public Utilities Commissioners to argue against the use of RECs and implication that community choice aggregators (CCAs) are not moving forward increased renewables generation. This new study appears to land on the side of the CCAs which have argued that even relying on RECs in the short run have a positive effect reducing GHG emissions in the West.

Two recent reports highlight the benefits of using “reverse auctions”. In a reverse auction, the buyer specifies a quantity to be purchased, and sellers bid to provide a portion of that quantity. An article in Utility Dive summarizes some of the experiences with renewable market auctions. A separate report in the Review of Environmental Economics and Policy goes further to lay out five guidelines:

This policy prescription requires well-informed policy makers balancing different factors–not a task that is well suited to a state legislature. How to develop such a coherent policy can done in two ways. The first is to let the a state commission work through a proceeding to set an overall target and structure. But perhaps a more fruitful approach would be to let local utilities, such as California’s community choice aggregators (CCAs) to set up individual auctions, maybe even setting their own storage targets and then experimenting with different approaches.

California has repeatedly made errors by overly relying on centralized market structures that overcommit or mismatch resource acquisition. This arises because a mistake by a single central buyer is multiplied across all load while a mistake by one buyer within a decentralized market is largely isolated to the load of that one buyer. Without perfect foresight and a distinct lack of mechanisms to appropriately share risk between buyers and sellers, we should be designing an electricity market that mitigates risks to consumers rather than trying to achieve a mythological “optimal” result.

I posted this response on EDF’s blog about energy storage:

This post accepts too easily the conventional industry “wisdom” that the only valid price signals come from short term responses and effects. In general, storage and demand response is likely to lead to increased renewables investment even if in the short run GHG emissions increase. This post hints at that possibility, but it doesn’t make this point explicitly. (The only exception might be increased viability of baseloaded coal plants in the East, but even then I think that the lower cost of renewables is displacing retiring coal.)

We have two facts about the electric grid system that undermine the validity of short-term electricity market functionality and pricing. First, regulatory imperatives to guarantee system reliability causes new capacity to be built prior to any evidence of capacity or energy shortages in the ISO balancing markets. Second, fossil fueled generation is no longer the incremental new resource in much of the U.S. electricity grid. While the ISO energy markets still rely on fossil fueled generation as the “marginal” bidder, these markets are in fact just transmission balancing markets and not sources for meeting new incremental loads. Most of that incremental load is now being met by renewables with near zero operational costs. Those resources do not directly set the short-term prices. Combined with first shortcoming, the total short term price is substantially below the true marginal costs of new resources.

Storage policy and pricing should be set using long-term values and emission changes based on expected resource additions, not on tomorrow’s energy imbalance market price.

From Utility Dive: The Salem NGS Unit 2 in New Jersey shutdown due to ice forming in its cooling water intake during the latest polar vortex event.

Texas generated 30% of its electricity last year with carbon-free resources (mostly wind.) Coals has shrunk over the last decade from 37% to 25%.

PG&E spends $275 million a year on energy efficiency investments that reduce demand by 100 MW. It also spends $65 million a year on demand response to reduce peak loads by 400 MW. If we assume that energy efficiency investments are effective an average of 12 years the incremental cost of those investments is $66 per MWH (6.6 cents per kWh). For demand response the incremental cost, which should match the market value, is $163 per kilowatt-year (or $13.60 per kW-month). Both of these values are reasonable investments for long-term resources.

Yet, PG&E argues in the PCIA exit fee proceeding and its annual ERRA generation cost proceeding that the appropriate market valuation for its resources are the short-term fire sale values that it realizes in the daily markets. According to PG&E, customers do not realize any additional value from holding these resources beyond what those resources can be bought and sold for the CAISO markets and in bilateral short-term deals.

So we are left with the obvious question: Why is PG&E continuing to invest in energy efficiency and demand response if the utility states that it can meet all of its needs in the short-term markets? This hypocrisy is probably best explained by PG&E manipulating the regulatory process. PG&E’s proposed “market valuation” sets the exit fee for community choice aggregation (CCA) at a high level. Instead, that market valuation should reflect how much CCAs have saved bundled customers in avoided procurement, and what PG&E pays for adding new resources.

Kevin Novan from UC Davis wrote an article in the University of California Giannini Foundation’s Agriculture and Resource Economics Update entitled “Should Communities Get into the Power Marketing Business?” Novan was skeptical of the gains from community choice aggregation (CCA), concluding that continued centrally planned procurement was preferable. Other UC-affiliated energy economists have also expressed skepticism, including Catherine Wolfram, Severin Borenstein, and Maximilian Auffhammer.

At the heart of this issue is the question of whether the gains of “perfect” coordination outweigh the losses from rent-seeking and increased risks from centralized decision making. I don’t consider myself an Austrian economist, but I’m becoming a fan of the principle that the overall outcomes of many decentralized decisions is likely to be better than a single “all eggs in one basket” decision. We pretend that the “central” planner is somehow omniscient and prudently minimizes risks. But after three decades of regulatory practice, I see that the regulators are not particularly competent at choosing the best course of action and have difficulty understanding key concepts in risk mitigation.By distributing decision making, we better capture a range of risk tolerances and bring more information to the market place. There are further social gains from dispersed political decision making that brings accountability much closer to home and increases transparency. Of course, there’s a limit on how far decentralization should go–each household can’t effectively negotiate separate power contracts. But we gain much more information by adding a number of generation service providers or “load serving entities” (LSE) to the market.

I found several shortcomings with with Novan’s article that would change the tenor. I take each in turn:

I was on the City of Davis Community Choice Energy Advisory Committee, and I am testifying on behalf of the California CCAs on the setting of the PCIA in several dockets. I have a Ph.D. from Berkeley’s ARE program and have worked on energy, environmental and water issues for about 30 years.

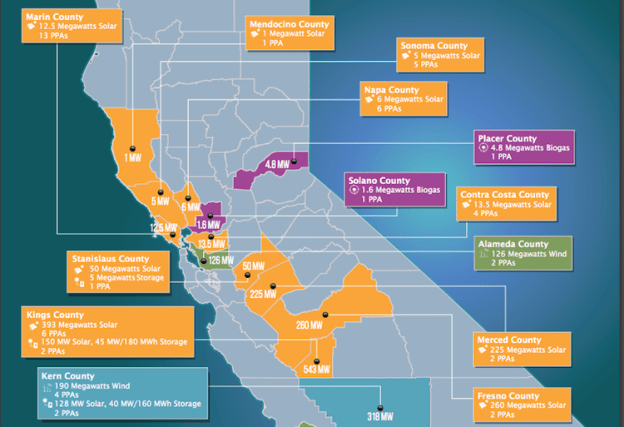

California’s community choice aggegrators (CCAs) are on track to meet their state-mandated renewable portfolio standard obligations. PG&E, SCE and SDG&E have not signed significant new renewable power capacity since 2015, while CCAs have been building new projects. To achieve zero carbon electricity by 2050 will require aggressive plans to procure new renewables soon.

All Things Solar and Electric

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

This blog is not necessarily about biking. It's about life that is lived locally, at a human pace.

Energy, Environment and Policy

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Examining State Authority in Interstate Electricity Markets

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Economic insight and analysis from The Wall Street Journal.

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

A few thoughts from John Fleck, a writer of journalism and other things, living in New Mexico

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

Tips and tricks on programming, evolutionary algorithms, and doing research

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water

A blog about water resources and law

Musings from M.Cubed on the environment, energy and water