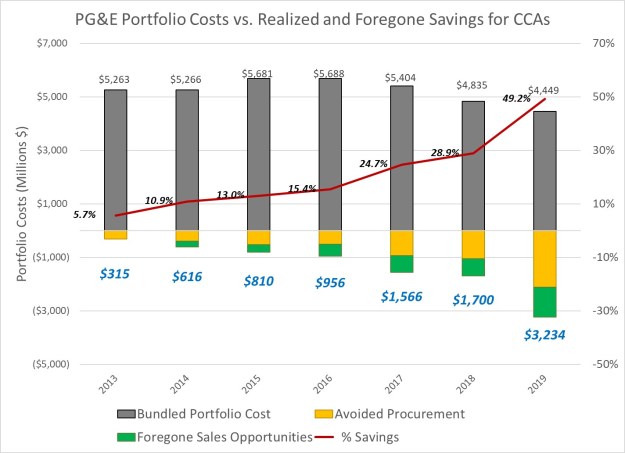

When community choice aggregators take up serving PG&E customers, PG&E saves the cost of having to procure power for the departed load. Instead the CCAs bear that cost for that power. The savings to PG&E’s bundled customers are not fully reflected when calculating the exit fee (known as the power charge indifference adjustment or PCIA) for those CCAs. As a result, the exit fee does not reflect the true value that CCAs provide to PG&E and its bundled customers.

The chart above shows the realized and potential savings to PG&E from the departure of CCA customers. The realized part is the avoided costs of procuring resources to meet that load, shown in yellow. The second part is the foregone sales opportunity if PG&E had sold a portion of its portfolio to the CCAs at the going price when they departed. In 2019, these combined savings could have reached $3.2 billion if PG&E had acted prudently.

Many local governments launched CCAs to address their climate goals, and CCAs issued multiple requests for offers of RPS energy. However, PG&E failed to respond to this opportunity to sell excess renewable energy no longer needed to serve their customers. By deciding to hold these unneeded resources in a declining market, PG&E accumulated additional losses every year. Indeed, the assigned Judge on the exit-fee proceeding at the CPUC concluded that PG&E must benefit from “holding back the RECs [renewable energy credits] for some reason.”

This willingness to hold onto an unneeded resource that loses value every year is contrary to prudent management. However, shareholders, are shielded entirely from contract that are too costly, and only pay penalties for failing to meet RPS targets. Instead, ratepayers—both bundled and CCA—pay all of the excessive costs, and shareholders only have a strong incentive to over-procure using those ratepayer dollars to avoid any possibility of reduced shareholder profits. Holding these contracts also inflates the exit-fee departed customers must pay, making it harder for alternatives like public power and distributed generation to PG&E to thrive.

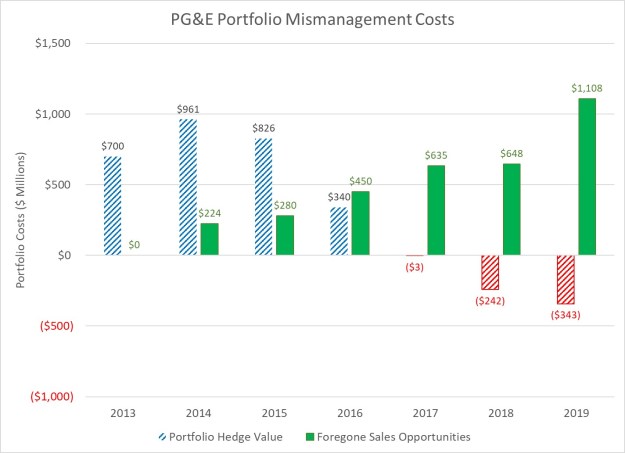

When Sonoma Clean Power launched in 2014, the average price of RPS energy was $128/MWh. It has declined every year, and now sits at $57/MWh. PG&E’s decision to not sell excess energy at 2014 prices, and to protect shareholders at the expense of ratepayers has cost customers over $3 billion dollars in the last 6 years as shown in the green columns below. As RPS prices continue to decline, and the amount of customer departing increases, this figure will continue to increase every year. Indeed, it surpassed $1.1 billion for 2019 alone.

Further, the hedging value of the RPS resources that PG&E listed as key attribute of holding these PPAs instead of disposing of them has diminished dramatically since PG&E pushed that as its strategy in its 2014 Bundled Procurement Plan. As shown in the chart above, the hedge value fell $1.3 billion from 2014 to 2019, from a high of $961 million to a burden of $343 million. PG&E’s hedge now adds $33/MWH to the cost of its renewables portfolio.

In comparison, Southern California Edison’s renewables portfolio costs just under $20/MWH less than PG&E’s. SCE did not rush into signing PPAs like PG&E and did not sign them for as long of terms as PG&E.