When it’s measured against $18,675 billion ($18.7 trillion) produced by the U.S. economy. The Heritage Foundation issued a report claiming the Obama Administration imposed $107 billion in new burdens over seven years. That sounds like a huge amount, but that’s only 0.6% (six-tenths of a percent) of the economy. And that’s spread over seven years which means that this the reduction in the GDP growth rate was only 0.08% (eight hundredths of a percent) per year. Against an annual average growth rate of over 2%, that’s a trivial amount. Another way to think of it is this way: if you had a dinner bill from Applebee’s for $19, would you not by dinner it if cost a dime more? Probably not–you wouldn’t even notice.

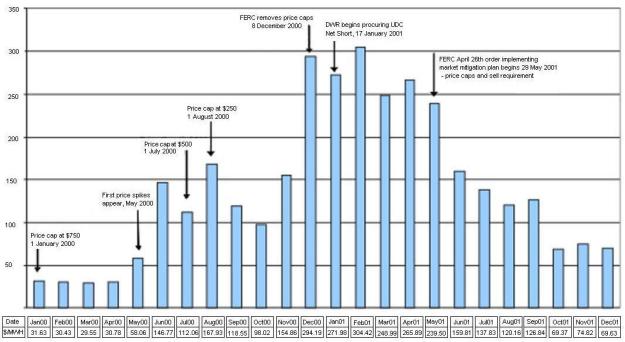

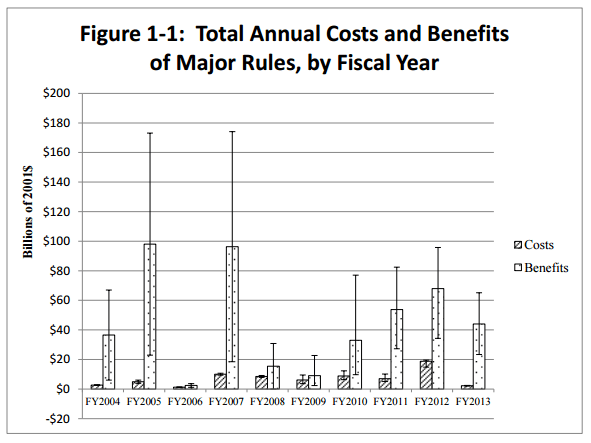

Plus, the HF’s estimate ignores the benefits of those regulations. This graphic from the OMB that shows the estimated relative benefits to costs of regulation.

I won’t dig too deeply into the Heritage Foundation’s analysis other than to make a couple of notes about about alternative perspectives that I am familiar with:

- Heritage Foundation claims that the Clean Power Plan has cost $7.2 billion as the single largest increment. Yet Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (which is much better qualified on this issue than the HF) just released a study showing the net financial “costs” of the various renewable portfolio standard (RPS) requirements is actually a benefit $47 to $109 billion. (And that ignores the environmental benefits identified in the report.)

- After the 2008 financial debacle, the industry was going to face increased regulation to reign in its behavior during the previous decade. So increased regulation under Dodd-Frank is to be expected. And the better question might be what is the drag on the economy from high financial-related transaction costs? One study found that transaction costs may be as high at 45% in the U.S. economy. The financial and legal sectors likely are a bigger drag than government regulation.

- On FCC net neutrality, see a previous post about how bigger corporations and economic concentration reduces innovation, which leads to reduced growth. Net neutrality is intended to fight that concentration.