PG&E released its 2022 Wildfire Mitigation Plan Update (2022 WMPU) That plan calls for $6 billion of capital investment to move 3,600 miles of underground by 2026. This is just over a third of the initial proposed target of 10,000 miles. Based on PG&E’s proposed ramping up, the utility would reach its target by 2030.

One alternative that could better control costs would be to install community and individual microgrids. Microgrids are likely more cost effective and faster means of reducing wildfire risk and saving lives. I wrote about how to evaluate this choice for relative cost effectiveness based on density of load and customers per mile of line.

Microgrids can mitigate wildfire risk by the utility turning off overhead wire service for extended periods, perhaps weeks at a time, during the highest fire risk periods. The advantage of a periodically-islanded microgrid is 1) that the highest fire risk coincides with the most solar generation so providing enough energy is not a problem and 2) the microgrids also can be used during winter storms to better support the local grid and to ride out shorter outages. Customers’ reliability may degrade because they would not have the grid support, but such systems generally have been quite reliable. In fact, reliability may increase because distribution grid outages are about 15 times more likely than system or regional outages.

The important question is whether microgrids can be built much more quickly than undergrounding lines and in particular whether PG&E has the capacity to manage such a buildout at a faster rate? PG&E has the Community Microgrid Enablement Program. The utility was recently authorized to build several isolated microgrids as an alternative to rebuilding fire-damaged distribution lines to isolated communities. Turning to local governments to manage many different construction projects likely would improve this schedule, like how Caltrans delegates road construction to counties and cities.

Controlling the costs of wildfire mitigation

Based on the current cost of capital this initial undergrounding phase will add $1.6 billion to annual revenue requirements or an additional 8% above today’s level. This would be on top of PG&E request in its 2023 General Rate Case for a 48% increase in distribution rates by 2023 and 78% increase by 2026, and a 31% increase in overall bundled rates by 2023 and 43% by 2026. The 2022 WMPU would take the increase to over 50% by 2026 (and that doesn’t’ include the higher maintenance costs). That means that residential rates would increase from 28.7 cents per kilowatt-hour today (already 21% higher than December 2020) to 36.4 cents in 2026. Building out the full 10,000 miles could lead to another 15% increase on top of all of this.

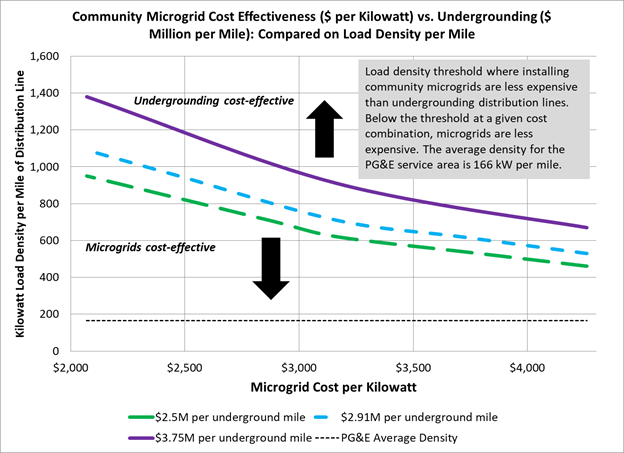

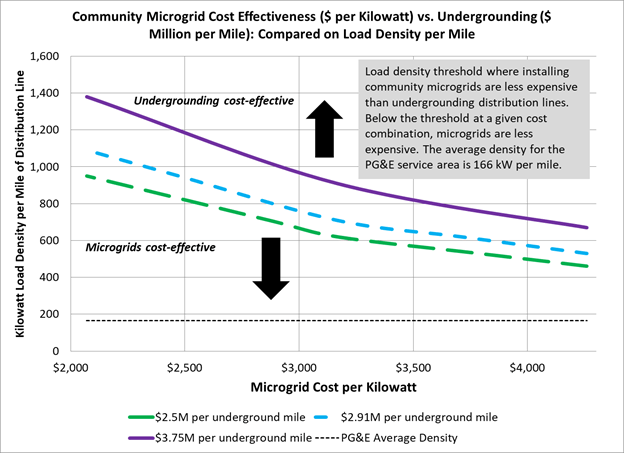

Turning to the comparison of undergrounding costs to microgrids, these two charts illustrate how to evaluate the opportunities for microgrids to lower these costs. PG&E states the initial cost per mile for undergrounding is $3.75 million, dropping to $2.5 million, or an average of $2.9 million. The first figure looks at community scale microgrids, using National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimates. It shows how the cost effectiveness of installing microgrids changes with density of peak loads on a circuit on the vertical axis, cost per kilowatt for a microgrid on the horizontal axis, and each line showing the division where undergrounding is less expensive (above) or microgrids are less expensive (below) based on the cost of undergrounding. As a benchmark, the dotted line shows the average load density in the PG&E system, combined rural and urban. So in average conditions, community microgrids are cheaper regardless of the costs of microgrids or undergrounding.

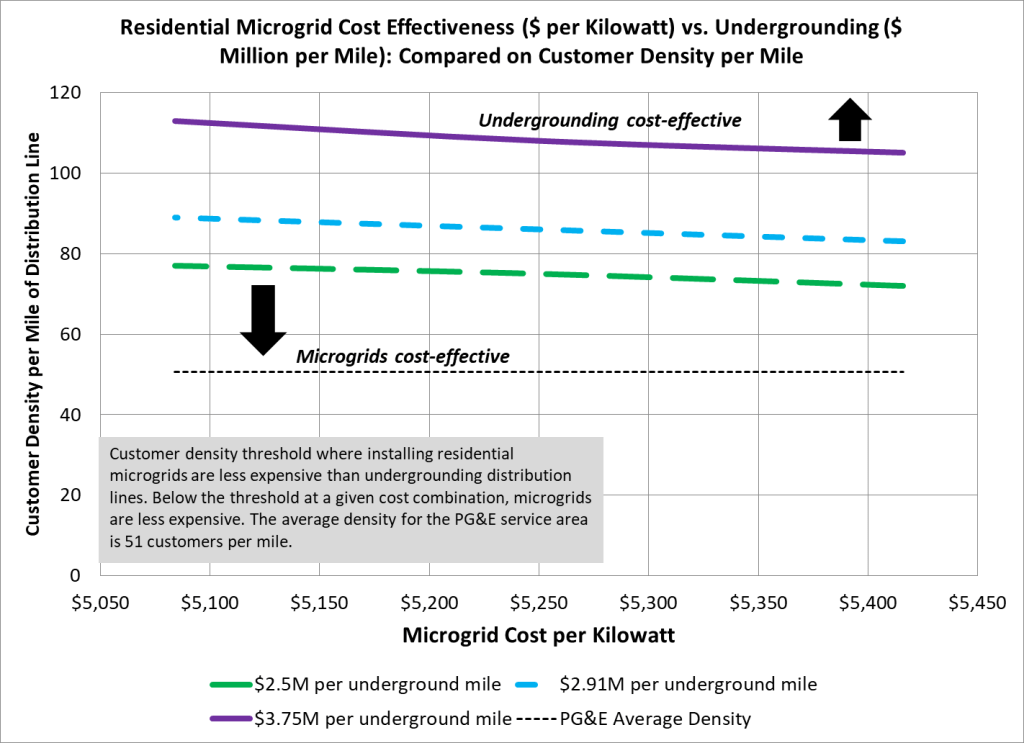

The second figure looks at individual residential scale microgrids, again using NREL estimates. It shows how the cost effectiveness of installing microgrids changes with customer density on a circuit on the vertical axis, cost per kilowatt for a microgrid on the horizontal axis, and each line showing the division where undergrounding is less expensive (above) or microgrids are less expensive (below). As a benchmark, the dotted line shows the average customer density in the PG&E system, combined rural and urban. Again, residential microgrids are less expensive in most situations, especially as density falls below 75 customers per mile.

A movement towards energy self-sufficiency is growing in California due to a confluence of factors. PG&E’s WMPU should reflect these new choices in manner that can reduce rates for all customers.

(Here’s my testimony on this topic filed by the California Farm Bureau in PG&E’s 2023 General Rate Case on its Wildfire Management Plan Update.)

PG&E is now planning to construct 30 microgrids to displace high risk distribution lines. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/solar/california-utility-clean-energy-microgrids-wildfires

LikeLike

https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/solar/california-utility-clean-energy-microgrids-wildfires

Expanding the grid to reach far-flung customers can be a costly fire hazard. So utilities like PG&E are testing out microgrids using solar, batteries, and generators.

Over the past few years, PG&E has increasingly opted for these “remote grids” as the costs of maintaining long power lines in wildfire-prone terrain skyrocket and the price of solar panels, batteries, and backup generators continues to decline. The utility has installed about a dozen systems in the Sierra Nevada high country, with the Pepperwood Preserve microgrid the first to be powered 100% by solar and batteries. The utility plans to complete more than 30 remote grids by the end of 2027.

Some larger projects have already been built. San Diego Gas & Electric has been running a microgrid for the rural California town of Borrego Springs since 2013, offering about 3,000 residents backup solar, battery, and generator power to bolster the single line that connects them to the larger grid, which is susceptible to being shut off due to wildfire risk.

Utilities have been far less friendly to customer-owned microgrids in general, however, seeing them as a threat to their core business model. Since 2018, California law has required the state Public Utilities Commission to develop rules to allow customers to build their own microgrids. But progress has been painfully slow, and only a handful of grant-funded projects have been completed.

Microgrid developers and advocates complain that the commission has put too many restrictions on how customers who own microgrids can earn money for the energy they generate when the grid remains up and running. Utilities contend that they need to maintain control over the portions of their grid that connect to microgrids to avoid creating more hazards.

LikeLike

PG&E installs a few more microgrids on a small scale to mitigate wildfire risks: https://investor.pgecorp.com/news-events/press-releases/press-release-details/2023/Innovation-in-Wildfire-Mitigation-PGE-Deploys-Its-First-100-Renewable-Remote-Grid/default.aspx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s a study looking at the relative value of wildfire risk mitigation of undergrounding compared to other options. The study doesn’t include microgrids but it could in this framework. https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/02/20/fighting-fires-in-the-power-sector/ https://haas.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/WP347.pdf

LikeLike

Wildfire risks in the US are soaring. Here’s what utilities can do. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/utility-mitigate-wildfire-risks-power-safety-shutoff-resilience/700139/ The solution proposed here are grid-centric rather than more holistically considering alternatives such as rural microgrids for the small number of customers who are served by a disproportionate share of at-risk lines.

LikeLike

Here’s an example of PG&E installing a microgrid in Sonoma to use in the manner suggested in this blog and in my testimony submitted in the PG&E and SDG&E GRCs. https://www.pepperwoodpreserve.org/2023/07/17/going-solar-in-the-wildland-urban-interface-wui-a-pge-pilot-project-at-pepperwood/

LikeLike

Map shows where California’s wildfires became more explosive https://www.sfchronicle.com/weather/article/climate-change-weather-map-18343696.php

LikeLiked by 1 person

The paper is discussed here- https://rogerpielkejr.substack.com/p/the-narrative-rules

…”Patrick Brown of The Breakthrough Institute published a commentary at The Free Press documenting how he and colleagues shaped their recent Nature paper on climate change and fire around a narrative that placed climate change at the center — even though they knew that fire disasters were not primarily about climate change.

Brown did not mince words:

To put it bluntly, climate science has become less about understanding the complexities of the world and more about serving as a kind of Cassandra, urgently warning the public about the dangers of climate change. However understandable this instinct may be, it distorts a great deal of climate science research, misinforms the public, and most importantly, makes practical solutions more difficult to achieve.”

I toured the King Fire years ago. I brought a melted motor casing with me to Ohio to remind me how hot the fire got.

LikeLike

First, I don’t know how increasing public focus on the impacts of climate change distracts from practical solutions. However the Breakthrough Institute has been both promoting impractical solutions like highly expensive nuclear power, and undermining the findings on climate research that in turn has given too many politicians an excuse to defer critical decisions. Michael Shellenberger is doing us a disservice, especially when he gets so many of his facts and concepts wrong.

On the other hand, I know how the need for academics to get published to gain tenure and promotions has led to widespread distortions in the literature. That the Stanford president got caught falsifying results shows how bad this situation has gotten. I consider legal and regulatory testimony to generally be of better quality than “peer-reviewed” articles that really haven’t faced adversarial review. If you’re going to be on a witness stand under hostile cross examination, you are much more likely to make sure that you’ve got a solid answer.

Academic journals also are highly biased toward publishing both “new” findings and “positive” outcomes over reproduced studies and “no difference” outcomes. If you’re an academic, why spend any time on research where the results won’t see the light of day? Pushing a narrative is just another aspect of this much larger problem.

LikeLike

100% concur with

“I consider legal and regulatory testimony to generally be of better quality than “peer-reviewed” articles that really haven’t faced adversarial review. If you’re going to be on a witness stand under hostile cross examination, you are much more likely to make sure that you’ve got a solid answer.”

I spent weeks providing discovery documents to legal on design control and product specification development and verification long ago. When your name is on design review documents saying a product will work in nursing homes and hospitals you should be very confident in your work.

I had major issues with the “affordable RE goals” that CA has been following as the affordable part of the goal was abandoned. The plan to provide sufficient energy via the grid to rural areas in the winter with single digit and low teen capacity factors PV and CSP generation were part of the reason for our leaving the state.

LikeLike

PG&E decides that vegetation management won’t reduce its wildfire risk significantly. https://www.cbsnews.com/sacramento/news/pg-e-cuts-tree-trimming-program-it-says-was-ineffective-in-fire-mitigation/

https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/tree-trimming-declared-ineffective-pg-203852156.html

LikeLike

Another study showing that using microgrids can be cost effective to reduce wildfire risk. However, it uses only retail rates as the metric (and current ones at that) rather than avoided costs of undergrounding: Study: Microgrids Could Reduce California Power Shutoffs—to a Point – https://insideclimatenews.org/news/07072023/study-microgrids-could-reduce-california-power-shutoffs-to-a-point/

LikeLike

PG&E is proposing to spend $18 billion for wildfire risk mitigation between 2023 and 2025: https://www.utilitydive.com/news/pge-corp-ceo-poppe-mitigation-measures-wildfire-season-risk-bury-power-lines/649525/ and https://www.utilitydive.com/news/pge-sce-vegetation-management-resilience-california-wildfires/646163/

LikeLike

Pingback: Retail electricity rate reform will not solve California’s problems | Economics Outside the Cube

Letter to the editor in the San Francisco Chronicle on this topic: https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/letterstotheeditor/article/pge-power-line-undergrounding-17883516.php

LikeLike

PG&E and SCE filed their 2023 Wildfire Managements Plans, asking for $25 billion through 2026 to underground their distribution lines.

– Pacific Gas & Electric is planning to invest roughly $18 billion to protect its electric grid against the threat of wildfires through 2025, according to a plan filed Monday by the utility with California’s Office of Energy Infrastructure Safety.

– Southern California Edison’s plan, meanwhile, estimated spending around $5.8 billion on wildfire mitigation strategies in its service territory, on measures such as installing covered conductors and transferring power lines underground in areas where the risk of fires is particularly high.https://www.utilitydive.com/news/pge-sce-vegetation-management-resilience-california-wildfires/646163/

LikeLike

Pingback: In the LA Times – looking for alternative solutions to storm outages | Economics Outside the Cube

Alliant Energy in Wisconsin found that a microgrid was economically preferable to undergrounding a line to a rural community as a means of improving reliability: https://www.tdworld.com/distributed-energy-resources/article/21251517/community-microgrid-a-first-for-wisconsin

LikeLike

An NSF study suggests that undergrounding in coastal areas could reduce the vulnerability of grids to extreme weather. However, a good question is whether installing microgrids could be more cost effective while delivering similar benefits. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/coastal-utilities-power-outages-underground-lines-nsf-study/631842/

LikeLike

Western Australia is pursuing microgrids to replace rural distribution investment.

https://www.energy-storage.news/western-australia-putting-1000-pv-plus-battery-standalone-power-systems-into-remote-and-rural-areas/

LikeLike

Pingback: Close Diablo Canyon? More distributed solar instead | Economics Outside the Cube

Pingback: What rooftop solar owners understand isn’t mythological | Economics Outside the Cube

Pingback: A reply: two different ways California can keep the lights on amid climate change | Economics Outside the Cube

The State Auditor issues a report criticizing PG&E’s proposed plan as inadequate and mistargeted: http://auditor.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2021-117.pdf

“Among the nearly 40,000 miles of bare power lines in high fire-risk areas, the state’s utilities have only completed hardening projects on just 1,540 miles of lines, according to the report.”

LikeLike

Pingback: PG&E takes a bold step on enabling EV back up power, but questions remain | Economics Outside the Cube

Pingback: Are PG&E’s customers about to walk? | Economics Outside the Cube