A cornerstone policy meant to promote energy efficiency is now being used as a weapon against energy savings. Decoupling the recovery of utilities’ costs and profits from electricity sales was intended to remove utilities’ opposition to promoting California’s resource loading order of using energy efficiency and distributed energy resources first.[1] Instead, protecting those revenue requirements and the associated utility profits, thus avoiding financial risk to shareholders, has become the paramount objective of the state’s decoupling policy at the expense of both reducing dependence on utility generation and increasing consumer sovereignty.[2] We are told that we need to increase our energy consumption to reduce the energy rates for those who have not reduced their utility purchases. The intent of decoupling has been turned on its head.

The premise of the ”cost shift” argument that asserts saving energy by one customer causes higher rates for other customers relies on an interpretation of decoupling whereby utility shareholders are shielded from suffering any financial losses caused by consumers turning elsewhere to find their energy services. This is one logical extension of decoupling, albeit not the one intended by those who originated this concept. Under this flawed rubric, each customer has an obligation to pay a share of the utility’s fixed and stranded costs. When a customer reduces their usage and their electricity bill, they are shirking this obligation according to the cost-shift argument.

Using the underlying rationale that utilities are guaranteed to recover their costs once approved by the CPUC and FERC, whether a customer-installed resource has a cost more or less than the social marginal cost is irrelevant unless that marginal cost is higher than the retail rate. Under this reasoning the customer owes the full amount of the retail rate and only receives a credit for saving energy that cannot exceed the marginal cost. The customer still owes the difference between the retail rate and the marginal cost and other customers must pick up that foregone sales revenue from the savings. Once a utility is authorized to collect a set amount of revenues, a customer has no escape from the corporate burden.

That presumption eliminates the ability to use market discipline through consumer choice to control rates (except moving out of state or to a municipal utility area). Under this reasoning, the only means of containing utility rates and mitigating bills is via regulatory action by the CPUC and FERC.

The problem is that regulators were supposed to strictly cap utility spending so that consumers could make their own choices about how to best meet their energy needs.[3] The utilities discovered that the regulators were not so vigilant and that the utilities could easily justify added utility-owned resources that were rolled into revenue requirements. The recovery of those costs was then protected from risk of either competition from customer resources or prudency review by policies implementing decoupling.

As a result, California’s utility rates have skyrocketed over the last two decades, with grid costs rising four times faster than inflation. These have reached crisis levels and state policy makers are desperately searching for easy solutions. Hence, the “cost shift” myth identifies the “true villains”—those customers who thought they were doing the right thing. Now they need to be punished.

When faced with declining sales and revenues, every other business cannot simply demand that customers make up the difference between the business’ current costs and its falling revenues. The business instead must either cut costs or provide a better service or product that attracts back those or other customers. The innovation motivated by this “creative destruction” as Joseph Schumpeter described it is at the core of the benefits we accrue from a market economy. Hinder that process and we get stagnation. The phased deregulation of the electricity market started with the 1978 PURPA is an important example of innovation was unleashed by removing the utilities’ ability to veto customers’ investments in their own resources. Without PURPA and the subsequent reforms, we would never had the technological revolution that both gives cost effective renewable energy resources and customers more control over their own energy use.

“Fixed” costs are not an explanation for rising rates

We also know that the supposed “fixed” costs of the utility system are not large. Generation and transmission resources are constantly redeployed among customers which is normal market functionality; these are not fixed costs, rather they are reallocated to customers who use more of those facilities. This is why grocery stores don’t charge customers to simply enter a store where 80% of the costs are don’t change with individual sales. Even in the distribution circuits, customers share most of the network with other customers; these costs are not fixed per-customer. Cell companies rarely require more than 12-month contracts with similar cost structures. (Three-year contracts are for paying off new phones and can be avoided by purchasing unlocked phones.)

The facts are that the various policy program costs are about the same as they have been for two decades at 10% of rates (and within that portion, energy efficiency should be classified as a resource cost just like generation), and the lion’s share of wildfire-related costs, which are only another 10%, were added four years ago and have risen only slightly since. Meanwhile PG&E increased its rates 50% over the last four years and the other two have or will increase their rates substantially.

The CPUC issued an order that the utilities impose a fixed charge of $24 per month for standard residential customers to cover those purported fixed costs. That’s approximately equal to the share of utility costs that might be considered fixed or related to state policy directives.

Rapidly rising rates is evidence that marginal costs are higher than retail rates and customer investment in new resources saves all ratepayers money

A key premise of the cost-shift argument is that these customers’ loads now being met by energy efficiency and DERs can be served by the existing utility system at little additional cost. In other words, these customers departed a system already built to accommodate their usage. That’s incorrect as one customer’s reduced load is an opportunity for another customer’s increased load to be served without an additional generation, transmission and distribution investment at today’s inflated costs. My more efficient refrigerator makes room for my neighbor’s hot tub, electric vehicle, or perhaps a needed medical appliance.

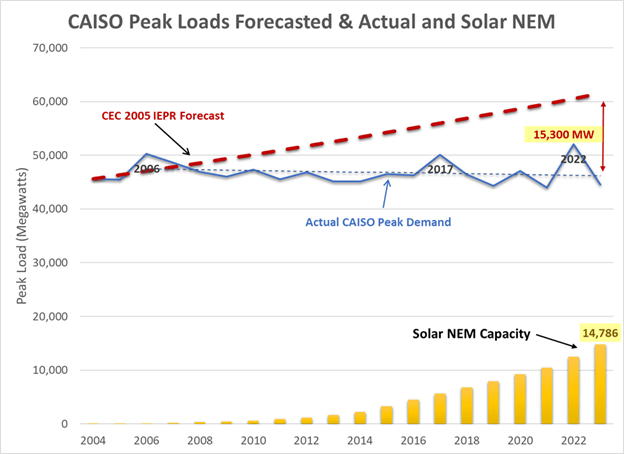

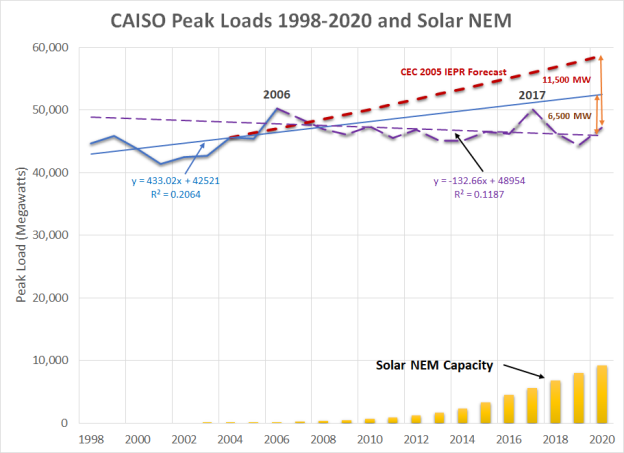

This premise overlooks that these customer resources have met at least a quarter on the energy demand since 2000. The true customer peak is three hours earlier and at least 12,000 megawatts higher than the metered CAISO peak. Based on historic utility costs over that period, annual utility revenue requirements would have increased $14 billion. California already struggled to bring on enough renewable energy over that period—the costs and environmental consequences of using utility generation would likely be even higher.

Claims that customers who save energy cause higher bills for other customers is premised on the unfounded notion that customers are departing from an already existing system built to accommodate their growing future demand. The cost shift analysis starts with today’s situation and then assumes that a customer who installs energy efficiency or rooftop solar is leaving a system already built to serve their current load.

Customers have also added additional loads, including more than one million electric vehicles. But for the reduction in loads from customer-installed resources, these additional loads would have required billions of dollars of investment in power supply and distribution capacity. Now, in many cases utilities built the additional capacity anyway – and it is a shortcoming of regulation that these costs were allowed into customer rates when the needed capacity was supplied by customer resources.

The fact is that a utility system is an aging and dynamic network that is constantly retiring and acquiring equipment to serve an ever-changing group of customers. For California, loads were forecasted to grow another 20% from 2005 to now. Instead, those loads have been flat as consumers have acquired their own resources, including LED lights, insulation, smart thermostats, double paned windows, insulation or solar panels. The metered peak shifted three hours later in the day, but the true customer peak still occurs mid-afternoon but it is met by customer-owned resources instead. A fifth of the true customer peak is now served by rooftop solar and a quarter of the state’s energy load comes from energy efficiency plus DERs. Much of that solar output is captured costlessly in hydro storage and used to meet that later peak. Any analysis must look at what it would have cost over those two decades to build the resources to serve those loads that instead are now served by individually-invested savings and generation.

We know that generation costs were significantly higher than that today’s costs (thanks to innovation) and that resources located at the point of use saves 30% or more in avoided peak losses and reserve power capacity. We know that those customer resources displaced adding new transmission that costs three times more than the average that is charged in retail rates. We know that the utilities consistently overforecasted the need for distribution infrastructure without consequence, and that the transmission and distribution rate components increased about 300% over the last two decades which is four times faster than inflation. Meanwhile, we also know that utility rates increased at the same pace as utility costs reflected in revenue requirements. This is important because if a other ratepayers were picking up the bills for customers who conserve and self generate, the rates would be increasing faster than revenue requirements as demand decreased. This is the essential element of the “death spiral” concept. There is no evidence of a death spiral yet.

The belief that these “departed” loads could have been served at little additional cost is unfounded based on the empirical evidence. If we conservatively use the average retail generation rate or 8.8 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2023 as representative of the true marginal cost,[4] add 12.5 cents per kilowatt-hour for the marginal cost of transmission, and then add an average of 4.4 cents per kilowatt-hour for avoided distribution costs from the utilities general rate case applications, the base avoided cost is 25.7 cents per kilowatt-hour. We then adjust the generation and transmission costs for 7% line losses and a 15% reserve margin, we are at 30.6 cents per kilowatt-hour for the actual marginal cost at the customer meter. In comparison, the average retail rate was only 27.8 cents per kilowatt in 2023 so customers investing in energy efficiency and rooftop solar are reducing incremental costs by 10%. And of course, this does not include environmental benefits, local economic activity or improved local energy resiliency. The total cost to serve the 89,000 gigawatt-hours saved would be $17 billion or a 30% increase in revenue requirements.

As is often the case, diagnosing the problem doesn’t mean that we have an immediate solution. That said, the objective should be to put utility shareholders at risk for excessive investments made based on optimistic growth forecasts. Having “used and useful” standards for asset utilization rates and unit-of-production depreciation are ways of extending cost recovery that lowers rates. However, those types of solutions are likely to move utilities back to opposing EE programs. The best solution is to create a competitive EE utility like the NW Energy Efficiency Alliance.

Today, we see that California is still struggling to bring on enough clean energy resources to meet its ambitious climate change mitigation goals. Diablo Canyon’s retirement was delayed and the state is not even approaching the threshold for installing renewables to meet the SB 100 clean energy target of 100% by 2045. The only viable alternatives are greater reliance on aggressive energy efficiency paired with electrification and customer-owned renewable generation. Misinterpreting the intention of decoupling should not be used as a barrier to reaching our goals.

[1] California first instituted decoupling in 1978 and then paused it in 1996 for restructuring. The system was restarted in 2002.

[2] It literally takes killing customers to put a utility at financial risk. See “ SDG&E Customers Should Not Pay for 2007 Wildfires: SCOTUS,” NBC 7 News, https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/local/us-supreme-court-sdge-wildfires-costs-lines-utility-fire-damage/1966157/, October 8, 2019; “PG&E receives maximum sentence for 2010 San Bruno explosion,” ABC 7 News, https://abc7news.com/post/pg-e-receives-maximum-sentence-for-2010-san-bruno-explosion/1722674/, January 28. 2017; “Ex-PG&E execs to pay $117M to settle lawsuit over wildfires,” AP News, https://apnews.com/article/wildfires-business-fires-lawsuits-california-450c961a4c6b467fcfb5465e7b9c5ae7, September 29, 2022; “PG&E Pleads Guilty On 2018 California Camp Fire: ‘Our Equipment Started That Fire’,” NPR CapRadio, https://www.npr.org/2020/06/16/879008760/pg-e-pleads-guilty-on-2018-california-camp-fire-our-equipment-started-that-fire, June 16, 2020. SCE may be facing a similar risk after the Easton Fire in January 2025. “Southern California Edison likely to incur ‘material losses’ related to Eaton fire, executive says,” LA Times, https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2025-04-30/edison-earnings-eaton-fire-losses, April 30, 2025.

[3] Decoupling delinked profits from actual sales and instead linked them to forecasted sales used to justify infrastructure investment. This removed the risk of overforecasting sales and perhaps falling short on recovering costs. And we see evidence of that practice in both PG&E’s and SCE’s forecasts used to justify investments from 2009 to 2018. The regulatory failure is that the CPUC didn’t go back and audit whether the investments were justified given that the sales didn’t materialize. Decoupling only works with a regulatory scheme that gives strong incentives for cost control.

[4] The 2024 rates were much higher for the utilities but it’s more difficult to calculate the average.