The California Public Utilities Commission’s (CPUC) Public Advocates Office (PAO) issued in August 2024 an analysis that purported to show current rooftop solar customers are causing a “cost shift” onto non-solar customers amounting to $8.5 billion in 2024. Unfortunately, this rather simplistic analysis started from an incorrect base and left out significant contributions, many of which are unique to rooftop solar, made to the utilities’ systems and benefitting all ratepayers. After incorporating this more accurate accounting of benefits, the data (presented in the chart above) shows that rooftop solar customers will in fact save other ratepayers approximately $1.5 billion in 2024.

The following steps were made to adjust the original analysis presented by the PAO:

- Rates & Solar Output: The PAO miscalculates rates and overestimates solar output. Retail rates were calculated based on utilities’ advice letters and proceeding workpapers. They incorporate time-of-use rates according to the hours when an average solar customer is actually using and exporting electricity. The averages are adjusted to include the share of net energy metering (NEM 1.0 and 2.0) and net billing tariff (NBT or “NEM 3.0”) customers (8% to 18% depending on the utility) who are receiving the California Alternate Rates for Energy program’s (CARE) low-income rate discount. (PAO assumed that all customers were non-CARE). In addition, the average solar panel capacity factor was reduced to 17.5% based on the state’s distributed solar database.[1] Accurately accounting for rates and solar outputs amounts to a $2.457 billion in benefits ignored by the PAO analysis.

- Self Generation: The PAO analysis included solar self-consumption as being obligated to pay full retail rates. Customers are not obligated to pay for energy to the utility for self generation. Solar output that is self-consumed by the solar customer was removed from the calculation. Inappropriately including self consumption as “lost” revenue in PAO analysis amounts to $3.989 billion in a phantom cost shift that should be set aside.

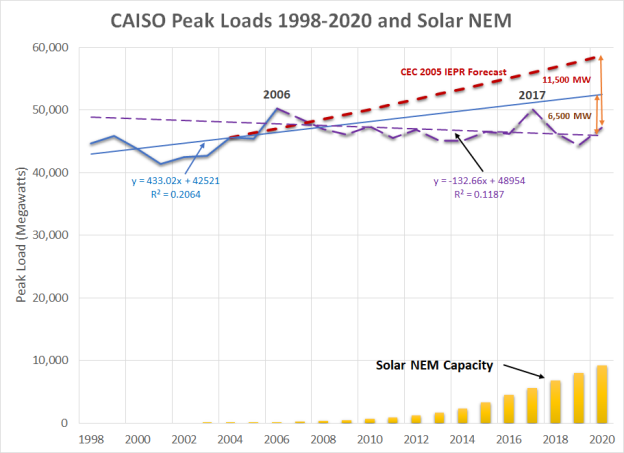

- Historic Utility Savings: The PAO fails to account for the full and accurate amount of savings and the shift in the system created by rooftop solar that has lowered costs and rates. The historic savings are based on distributed solar displacing 15,000 megawatts of peak load and 23,000 gigawatt-hours of energy since 2006 compared to the California Energy Commission’s (CEC) 2005 Integrated Energy Policy Report forecast.[2] Deferred generation capacity valuation starts with the CEC’s cost of a combustion turbine[3] and is trended to the marginal costs filed in the most recent decided general rate cases. Generation energy is the mix of average California Independent System Operator (CAISO) market prices in 2023,[4] and utilities’ average renewable energy contract prices.[5] Avoided transmission costs are conservatively set at the current unbundled retail transmission rate components. Distribution investment savings are the weighted average of the marginal costs included in the utilities’ general case filings from 2007 to 2021. Accounting for utility savings from distributed solar amounts to $2.165 billion ignored by the PAO’s calculation.

- Displaced CARE Subsidy: The PAO analysis does not account for savings from solar customers who would otherwise receive CARE subsidies. When CARE customers buy less energy from the utilities, it reduces the total cost of the CARE subsidy born by other ratepayers. This is equally true for energy efficiency. The savings to all non-CARE customers from displacing electricity consumption by CARE customers with self generation is calculated from the rate discount times that self generation. Accounting for reduced CARE subsidies amounts to $157 million in benefits ignored by the PAO analysis.

- Customer Bill Payments: The PAO analysis does not account for payments towards fixed costs made by solar customers. Most NEM customers do not offset all of their electricity usage with solar.[6] NEM customers pay an average of $80 to $160 per month, depending on the utility, after installing solar.[7] Their monthly bill payments more than cover what are purported fixed costs, such as the service transformer. A justification for the $24 per month customer charge was a purported under collection from rooftop solar customers.[8] Subtracting the variable costs represented by the Avoided Cost Calculator from these monthly payments, the remainder is the contribution to utility fixed costs, amounting to an average of $70 per month. (In comparison for example, PG&E proposed an average fixed charge of $51 per month in the income graduated fixed charge proceeding.[9]) There is no data available on average NBT bills, but NBT customers also pay at least $15 per month in a minimum fixed charge today.[10] Accounting for fixed cost payments adds $1.18 billion in benefits ignored by the PAO analysis.

The correct analytic steps are as follows:

NEM Net Benefits = [(kWh Generation [Corrected] – kWh Self Use) x Average Retail Rate Compensation [Corrected] )]

– [(kWh Generation [Corrected] – kWh Self Use) x Historic Utility Savings ($/kWh)]

– [CARE/FERA kWh Self Use x CARE/FERA Rate Discount ($/kWh)]

– [(kWh Delivered x (Average Retail Rate ($/kWh) – Historic Utility Savings $(kWh))]

NBT Net Benefits = [(kWh Generation [Corrected] – kWh Self Use) x Average Retail Rate Compensation [Corrected])]

– [(kWh Generation [Corrected] – kWh Self Use) x Avoided Cost (Corrected) ($/kWh)]

– [CARE/FERA kWh Self Use x CARE/FERA Rate Discount ($/kWh)]

– [(Net kWh Delivered x (Average Retail Rate ($/kWh) – Historic Utility Savings $(kWh))]

This analysis is not a value of solar nor a full benefit-cost analysis. It is only an adjusted ratepayer-impact test calculation that reflects the appropriate perspective given the PAO’s recent published analysis. A full benefit-cost analysis would include a broader assessment of impacts on the long-term resource plan, environmental impacts such as greenhouse gas and criteria air pollutant emissions, changes in reliability and resilience, distribution effects including from shifts in environmental impacts, changes in economic activity, and acceleration in technological innovation. Policy makers may also want to consider other non-energy benefits as well such local job creation and supporting minority owned businesses.

This analysis applies equally to one conducted by Severin Borenstein at the University of California’s Energy Institute at Haas. Borenstein arrived at an average retail rate similar to the one used in this analysis, but he also included an obligation for self generation to pay the retail rate, ignored historic utility cost savings and did not include existing bill contributions to fixed costs.

The supporting workpapers are posted here.

Thanks to Tom Beach at Crossborder Energy for a more rigorous calculation of average retail rates paid by rooftop solar customers.

[1] PAO assumed a solar panel capacity factor of 20%, which inflates the amount of electricity that comes from solar. For a more accurate calculation see California Distributed Generation Statistics, https://www.californiadgstats.ca.gov/charts/.

[2] This estimate is conservative because it does not include the accumulated time value of money created by investment begun 18 years ago. It also ignores the savings in reduced line losses (up to 20% during peak hours), avoided reserve margins of at least 15%, and suppressed CAISO market prices from a 13% reduction in energy sales.

[3] CEC, Comparative Costs of California Central Station Electricity Generation Technologies, CEC-200-2007-011-SF, December 2007.

[4] CAISO, 2023 Annual Report on Market Issues & Performance, Department of Market Monitoring, July 29, 2024.

[5] CPUC, “2023 Padilla Report: Costs and Cost Savings for the RPS Program,” May 2023.

[6] Those customers who offset all of their usage pay minimum bills of at least $12 per month.

[7] PG&E, SCE and SDG&E data responses to CALSSA in CPUC Proceeding R.20-08-020, escalated from 2020 to 2024 average rates.

[8] CPUC Decision 24-05-028.

[9] CPUC Proceeding Rulemaking 22-07-005.

[10] The average bill for NBT customer is not known at this time.